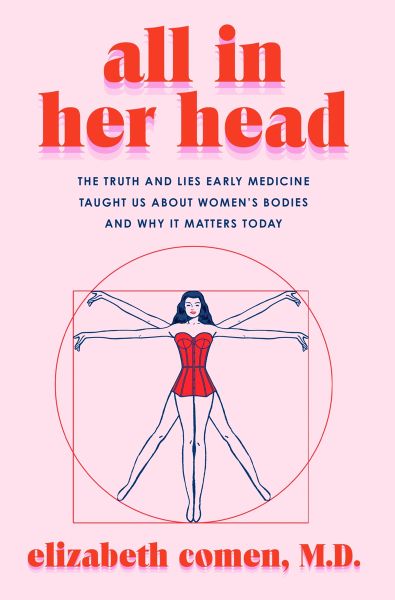

All in Her Head: The Truth and Lies Early Medicine Taught Us about Women's Bodies and Why It Matters Today

Memorial Sloan Kettering oncologist and medical historian Dr. Elizabeth Comen unveils the collective medical history of women, exploring how medicine has long misunderstood women's bodies and how these historical oversights continue to affect women's health today.

📝 Book Review

Throughout the long history of medicine, women’s bodies have been a misunderstood, overlooked, and oversimplified puzzle. When we open medical textbooks, the “standard human body” depicted is almost always male—male hearts, male brains, male symptoms, male drug dosages. Women’s bodies are treated as “special cases,” relegated to the narrow field of gynecology, as if apart from reproductive systems, women’s other organs are no different from men’s. This systematic medical sexism is not merely a historical legacy but a reality that persists today. Dr. Elizabeth Comen’s “All in Her Head” challenges this status quo by deeply excavating medical history, revealing how women’s bodies have been marginalized by medical knowledge systems and why we urgently need a new conversation about women’s health.

Dr. Comen herself is the ideal initiator of this conversation. As an oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College, she treats women cancer patients on the front lines daily, personally experiencing the consequences of gender blind spots in the medical system. Meanwhile, her training in history of science at Harvard University has equipped her with theoretical tools to critically examine the process of medical knowledge production. This dual identity as clinician and historian allows her to connect past and present from a unique perspective, linking historical medical fallacies with contemporary health challenges women face.

The book employs a clever structural framework: following the eleven organ systems of the human body, revealing one by one how each system has been understood through a gendered lens in medical history. This is not a simple rewriting of medical textbooks but a profound archaeological excavation of knowledge. Dr. Comen has pored over volumes of historical medical literature and journals, interviewed expert physicians across specialties, and combined her experience treating thousands of women patients to weave a complete picture of women’s medical history. She reveals not only medical knowledge itself but the power relations, social prejudices, and gender politics behind knowledge production.

From ancient Greek humoral theory to 19th-century hysteria diagnoses, from early anatomical imaginings of women’s bodies to the systematic exclusion of women from modern medical research, Dr. Comen traces a startling pattern: women’s bodily symptoms are often attributed to emotions, psychology, or “imagination.” The book’s title “All in Her Head” is an ironic reference to this historical pattern. When women patients complain of pain, fatigue, or other symptoms, doctors too easily attribute these to anxiety, depression, or “hysteria” rather than seriously seeking physical causes. This medical attitude not only delays diagnosis and treatment but, more fundamentally, denies women’s cognitive authority over their own bodies.

Dr. Comen pays particular attention to gender bias in medical research. Until 1993, the National Institutes of Health did not mandate that clinical trials must include female subjects. For decades before that, the vast majority of medical research used only male subjects, then applied the findings directly to female patients. This means our understanding of drug side effects, disease symptoms, and treatment protocols is largely based on data from male bodies. The physiological differences between women and men—from hormonal cycles to organ sizes, from metabolic rates to immune responses—were all ignored. The result is that women are more likely to suffer adverse drug reactions, more likely to be misdiagnosed or have delayed diagnoses, and pay a higher price in the medical system.

The example of cardiovascular disease is particularly stark. For a long time, heart disease was viewed as a “male disease,” and the classic symptoms of heart attack—chest pain radiating to the left arm—were summarized from male patients. But women’s heart attack symptoms are often different, potentially manifesting as nausea, back pain, extreme fatigue, or shortness of breath. Because doctors are not sufficiently familiar with women’s heart attack symptoms, many female patients’ heart attacks are misdiagnosed as anxiety disorders, indigestion, or menopausal symptoms. Even today, women’s mortality rate after heart attacks remains higher than men’s, partly due to this diagnostic delay. Dr. Comen points out that this is not a problem of medical technology but a gender blind spot in the medical knowledge system.

Pain management is another deeply gendered medical field. Research shows that pain reported by female patients is more likely to be underestimated or doubted by doctors, they wait longer for pain medication, and the pain treatment they receive is often inadequate. Behind this is an ancient medical assumption: women are more likely to “exaggerate” symptoms, women have higher pain thresholds (so their reported pain might be “not that serious”), or women’s pain is “psychological.” Through numerous cases, Dr. Comen demonstrates how this medical attitude causes women patients to suffer unnecessarily in illness, how serious diseases are delayed in diagnosis, and even how it leads to preventable deaths.

Endometriosis is a typical case. This disease, which affects about 10% of women, takes an average of 7-10 years to be diagnosed. During this long waiting period, women patients are often told “period pain is normal,” “just bear it,” “maybe it’s too much stress.” Their pain is minimized, their bodily perception questioned. Dr. Comen points out that this diagnostic delay is not only because the medical community has insufficient research on this disease but because women’s pain is systematically devalued in medical culture. If men also experienced monthly disabling pain, this disease would long ago have become a medical research priority.

Dr. Comen does not shy away from darker chapters in medical history. She documents in detail how medical experiments were conducted on women’s bodies, particularly on marginalized groups of women—enslaved Black women, incarcerated women, women in psychiatric institutions—without consent. One of the founders of modern gynecological surgery, J. Marion Sims, performed multiple experimental surgeries on enslaved Black women without anesthesia. This history is not just past atrocity; it reveals the intersection of power and race in medical knowledge production and how women—particularly women of color—were sacrificed in the name of medical progress.

But this book is not only critique but constructive. Dr. Comen emphasizes that revealing history is not to blame individual doctors or demonize the medical profession but to understand the roots of systematic problems and thereby promote real change. She calls for establishing a new medical epistemology, a mode of knowledge production that centers women’s experiences. This means medical research must include sufficient female subjects and analyze data by sex; medical education must teach students to recognize the importance of gender in physiology and pathology; clinical practice must take women patients’ complaints seriously rather than easily attributing them to psychological factors.

Dr. Comen also pays special attention to intersectionality. She points out that women are not a homogeneous group—race, class, sexual orientation, gender identity, and other factors all affect women’s experiences in the medical system. Black women’s maternal mortality rate is three times that of white women, transgender women face extremely high medical discrimination and violence, poor women struggle to access basic medical services. Any conversation about women’s health that does not consider these differences will repeat the mistakes of historical white middle-class feminism—representing all women with the experiences of some women.

As an oncologist, Dr. Comen’s discussion of breast cancer is particularly profound. She traces the evolution of breast cancer treatment, from the radical mastectomy of the late 19th century (which removed not only the breast but also the pectoralis major muscle and axillary lymph nodes) to today’s breast-conserving surgery plus radiation. This evolution is not only progress in medical technology but a transformation in understanding of women’s bodies and women’s autonomy. Early radical surgery was partly based on the assumption that women’s bodies could be drastically altered for “cure,” that women’s appearance and bodily integrity were less important than survival. The development of breast-conserving surgery, however, recognized that women’s concerns about their body image are not vanity but legitimate concerns closely related to quality of life.

Dr. Comen also discusses menopause—a physiological process almost every woman experiences yet has long been stigmatized in medicine. Menopause was once viewed as “decline,” “loss of femininity,” even the onset of “mental illness.” The history of hormone replacement therapy is full of controversy: from being overprescribed as a panacea for “eternal youth” to being demonized as a dangerous carcinogen. Dr. Comen calls for a more balanced, more scientific attitude toward menopause: it is not a disease but does bring symptoms that may need medical support; hormone therapy has its indications and risks and should be based on informed decisions about individual circumstances, not blanket prohibition or promotion.

The book also addresses emerging gender issues in contemporary medicine. For example, as our understanding of gender diversity deepens, how must medicine adjust? Transgender men may retain uteruses and ovaries and need gynecological care; transgender women may need prostate examinations. The traditional binary gender medical framework is no longer adequate to address this diversity. Dr. Comen believes this is precisely an opportunity to rethink the entire concept of gender in medicine: not simply categorizing everyone as “male” or “female” but understanding the complexity of gender and physiology, providing personalized medical services based on actual physiological characteristics rather than stereotypical gender assumptions.

The power of “All in Her Head” lies in its perfect combination of academic research, clinical experience, and personal narrative. Dr. Comen not only cites research data and historical documents but shares her patients’ stories—women whose diagnoses were delayed, women whose pain was not believed, women who felt ignored and disrespected in the medical system. These personal stories make abstract medical history concrete and urgent, reminding us this is not only a historical problem but a reality occurring every day.

This book is also a call to action. Dr. Comen calls on the medical community, policymakers, research funding agencies, and society as a whole to take concrete action: increase research funding for women-specific diseases; reform medical education curricula to include gender medicine content; raise clinicians’ awareness of gender bias; build more inclusive medical environments; and most importantly, listen to women patients’ voices and believe their perceptions of their own bodies.

For general readers, this book imparts important knowledge and power. Understanding gender bias in medical history can help women better advocate for their health rights. When a doctor tries to attribute your symptoms to anxiety, you can insist on more comprehensive testing; when you feel your pain is not being taken seriously, you know this is not your problem but the system’s problem; when you feel confused in medical decision-making, you have the right to request more information, seek second opinions, and participate in the decision-making process.

Dr. Comen’s writing combines academic depth with readability. She can explain complex medical concepts in accessible terms while maintaining analytical rigor. Her narrative is full of empathy, expressing deep sympathy for both historical women patients and modern women patients while maintaining understanding of the complex realities medical practitioners face. She does not simply condemn individual doctors but reveals systematic problems, calling for transformation of the entire medical system.

This book was published in 2024, coinciding with another critical moment for the women’s health movement in America. With the overturning of Roe v. Wade, reproductive rights face unprecedented threats; meanwhile, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed gender and racial inequalities in the healthcare system; social media allows more and more women to share their medical experiences, exposing systematic problems. Against this background, the publication of “All in Her Head” appears particularly timely and important. It not only reviews history but points toward the future: a medical system that truly centers women’s health is possible, but it requires all of us—doctors, researchers, patients, policymakers—to work together.

Ultimately, this book tells of the politics of epistemology: whose knowledge is considered valid? Whose bodily experience is viewed as normative? Who has the right to define health and illness? For centuries, the answers to these questions have pointed to men. Dr. Comen’s work is an important contribution to feminist medical historiography. It not only exposes past injustices but provides a roadmap for building a more just medical future. In this future, women’s bodies are no longer “special cases,” women’s symptoms are no longer attributed to being “all in her head,” and everyone can receive medical care based on the best scientific evidence and respect for the individual. This future is worth fighting for, and “All in Her Head” is an important weapon in this struggle.

Book Info

Related Topics

🛒 Get This Book

Buy on Amazon

Buy on Amazon Related Books

Book Discussion

Share your thoughts and opinions on this book and exchange insights with other readers

Join the Discussion

Share your thoughts and opinions on this book and exchange insights with other readers

Loading comments...