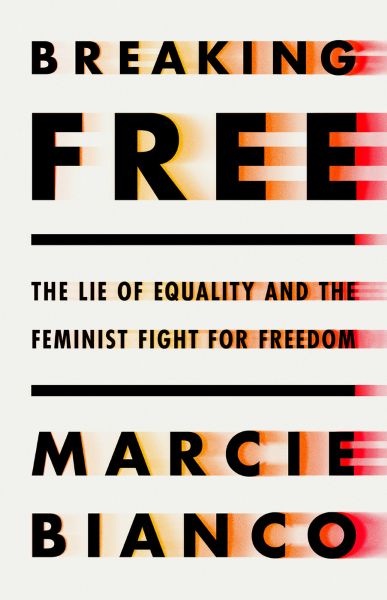

Breaking Free: The Lie of Equality and the Feminist Fight for Freedom

Culture writer Marcie Bianco boldly argues that 'equality' is a racist, patriarchal ideal that perpetuates women's systemic oppression and limits the possibilities of feminism—with a plan to transform the movement.

📝 Book Review

For more than a century, women have fought for equality. Yet, time and again, their battles have fallen short. Even so-called constitutionally-protected equal rights can be withdrawn by judges and undermined by legislators. But the greater problem lies in the notion of equality itself. In culture writer Marcie Bianco’s “Breaking Free,” she presents a radical and startling argument: equality itself is a lie, an illusory goal that cannot truly address historical forms of discrimination and oppression. More seriously, the pursuit of equality has actually become an ideological trap, locking women and disenfranchised communities into a chase for something perpetually unattainable.

Bianco’s starting point is a profound reflection on the history of the feminist movement. Since the 19th-century women’s suffrage movement, feminists have made “equality” their core demand. They demanded equal voting rights with men, equal property rights, equal educational opportunities, equal employment rights. These demands seemed revolutionary at the time, challenging legal and social structures that viewed women as appendages to men. However, Bianco points out that this struggle framed around “equality” had fundamental problems from the start: it set the male state as the standard, defining women’s goal as “catching up” to men.

The limitations of this way of thinking became increasingly apparent in the second half of the 20th century. The second wave of feminism achieved major victories in the 1960s and 1970s—the Equal Employment Opportunity Act, Title IX of the Education Amendments, Roe v. Wade—but these victories did not bring true liberation. Instead, women found themselves expected to “work like men” in the workplace while still bearing primary care responsibilities at home. The promise of equality became the reality of a double burden. Worse still, when women of color, working-class women, and queer women pointed out that this “equality” primarily benefited white middle-class heterosexual women, they were often marginalized by mainstream feminism.

Bianco traces the historical genealogy of the concept of “equality,” revealing how it is rooted in Enlightenment rationalism and liberal traditions—traditions that are themselves products of white male centrism. When America’s founders declared that “all men are created equal,” “men” actually referred only to property-owning white males. Women and enslaved Black people were excluded from this definition. Even when later amendments and legislation expanded the scope of “equality,” the structural limitations of this concept remained: it assumes a neutral, universal human subject, when in reality this subject is always defaulted to male, white, heterosexual, and able-bodied.

One of the book’s most powerful arguments is its analysis of how “equality” reinforces the binary gender system. When feminists demand “equality between men and women,” they inadvertently consolidate the notion that there are only two genders and the assumption that these two genders are fundamentally different. This framework cannot accommodate the experiences of non-binary, transgender, and gender non-conforming people. More importantly, it essentializes gender differences, making it impossible to challenge gender itself. Bianco points out that as long as we remain within the framework of “equality,” we can only make adjustments within the existing gender order, unable to imagine a world without gender oppression.

Bianco also deeply critiques how “equality” is used as a political tool to suppress more radical change. Whenever the feminist movement makes deeper demands—such as abolishing family structures, redistributing care work, challenging capitalism’s exploitation of women’s bodies—conservatives say “you already have equality, what more do you want?” Equality becomes a ceiling, a boundary used to define “reasonable” feminist demands. Any demands beyond equality are seen as “excessive,” “radical,” or “unrealistic.” This discourse effectively domesticates feminism, transforming a movement that originally had revolutionary potential into a reformist project.

So if not equality, what should feminism pursue? Bianco’s answer is: freedom. But the freedom she speaks of is not individualist liberal choice but a collective, radical freedom—freedom from the constraints of patriarchal structures, freedom to create new ways of living, freedom to define one’s own body and desires. This freedom is not about demanding to be “the same” as men but about refusing the premise that male experience is the norm.

Bianco draws inspiration from radical traditions overlooked by mainstream feminist history. She rediscovers the 19th-century free love movement, early 20th-century anarcha-feminists, and 1970s lesbian separatists—movements and thinkers who were not satisfied with fighting for equality within the existing system but attempted to create completely different modes of social relations. They rejected the institution of marriage, questioned the nuclear family, experimented with collective living, and challenged gender norms. While these experiments were often criticized as “unrealistic” or “extreme,” Bianco argues that it is precisely this radical imagination that can truly drive change.

The core section of the book proposes three “freedom practices” as concrete methods for women to reclaim bodily autonomy and power. The first practice is “bodily sovereignty.” Bianco argues that women must have complete control over their bodies—not just reproductive rights, but all aspects of sexuality, appearance, and health decisions. This means refusing all forms of bodily discipline, whether they come from patriarchy, capitalism, the medical system, or even the feminist movement itself. This is a more radical position than “my body, my choice” because it refuses to view the body as property that can be “owned,” instead understanding it as the foundation of subjectivity.

The second practice is “relational autonomy.” Bianco challenges liberal feminism’s emphasis on the independent individual, pointing out that humans are fundamentally interdependent beings. True freedom is not about not needing anyone but about being able to choose and create supportive, non-oppressive relationship networks. This includes reimagining the possibilities of intimate relationships, family structures, and community organization. Bianco pays particular attention to the redistribution of care work, arguing that as long as women continue to bear disproportionate care responsibilities, any form of “equality” is just an illusion.

The third practice is “political imagination.” Bianco calls on feminists to break free from the constraints of “realism” and dare to imagine radically different futures. This is not fantasy but recognition that our understanding of what is “possible” is limited by existing power structures. Every major social change in history—the abolition of slavery, women’s suffrage, the civil rights movement—was considered “impossible” before it was achieved. Bianco argues that the feminist movement must recultivate this utopian thinking, not as an escape from reality but as a prerequisite for changing reality.

Bianco pays particular attention to the intersectionality of race and class. She points out that white feminism’s pursuit of “equality” is often built on the exploitation of women of color and working-class women. When white middle-class women entered the workplace pursuing “equality,” who took care of their children and elderly? Often women of color and immigrant women, doing this devalued labor for low wages. True freedom must be freedom for all women, not just the privileged class. This requires us not only to challenge gender inequality but to challenge the entire economic and political system that produces inequality.

The book’s critique of contemporary feminist movements is particularly sharp. Bianco argues that much of contemporary feminism has been co-opted by neoliberalism, becoming a “lean in” philosophy of individual success. Women are encouraged to “build confidence,” “break the glass ceiling,” “become girl bosses,” as if individual career success equals feminist victory. This feminism not only ignores the structural barriers most women face but, worse, transforms feminism into a tool of capitalism. Bianco sharply points out that when corporate CEOs declare themselves feminists, this is not a feminist victory but a sign that feminism has been hollowed out.

Bianco also critiques the limitations of identity politics. While she fully supports the importance of marginalized groups speaking and being seen, she argues that contemporary identity politics often falls into the trap of “representation”—focusing on who sits at the power table rather than questioning the legitimacy of the table itself. Having more women CEOs, women politicians, women generals does not equal a freer society if these women uphold the same oppressive systems. True feminism should not be about getting women into existing power structures but about transforming or abolishing those structures.

“Breaking Free” also deeply explores the political reality after the overturning of Roe v. Wade. Bianco argues that this catastrophic setback precisely proves the fragility of the “equality” framework. For decades, the American feminist movement viewed abortion rights as a constitutionally guaranteed equal right, but this right ultimately proved easily revoked. Bianco argues that if we had from the beginning viewed reproductive autonomy as an inalienable freedom rather than a negotiable right, if we had built social and economic structures supporting this freedom rather than relying solely on legal decisions, the situation might be very different now. This is not blaming past activists but learning from history to provide different strategies for future struggles.

The final section of the book is a radical call to action. Bianco proposes concrete steps for how individuals and collectives can begin practicing “freedom feminism.” This includes building women-centered, non-hierarchical organizations; developing mutual aid networks and alternative economic forms; creating communities supporting radical lifestyles; imagining and depicting different futures in cultural production; refusing gender norms and expectations in daily life; and most importantly, building coalitions across differences based on shared anti-oppression commitments rather than shared identities.

Bianco’s writing style is bold and passionate, not shying away from controversy. She knows her arguments will cause discomfort, particularly among those who view “equality” as a core feminist value. But she believes this discomfort is necessary. If the feminist movement is to move forward, it must be willing to question its own fundamental assumptions, including those that seem self-evident. This is not a betrayal of feminism but loyalty to its original purpose—feminism should never be about demanding entry into the oppressor’s club but about abolishing all forms of oppression.

“Breaking Free” is a book that will provoke strong reactions—some will find it liberating, others will find it dangerous. But whether readers agree with all of Bianco’s arguments, the book successfully accomplishes its primary task: forcing us to rethink feminism’s most fundamental concepts and goals. In an era when women’s rights continue to be attacked and mainstream feminism seems increasingly powerless to respond, Bianco offers a different perspective—one more radical, more imaginative, and perhaps more hopeful.

The power of this book lies not only in its critique but in its vision. Bianco does not simply deconstruct “equality” but attempts to open new political possibilities for us. She invites us to imagine a society based not on “equality” with men but on everyone being able to develop freely, be free from oppression, and flourish in interdependence. This vision may seem distant or even impractical, but as Bianco reminds us, all great social changes in history were considered impossible before they were achieved. The task of feminism is not to adapt to reality but to change it.

Ultimately, “Breaking Free” is a passionate call to the feminist movement to reclaim its radical potential. Bianco argues that feminism should not be satisfied with moving pieces on patriarchy’s chessboard but should overturn the entire board. This requires courage, imagination, and commitment to fundamental change. But if we truly believe another world is possible, if we truly want to create freedom and dignity for all people—not just a few—then we have no choice but to break free from the shackles of “equality” and courageously pursue true freedom. This book is a roadmap for this journey, a challenging but hopeful guide to a new future for the feminist movement.

Book Info

Related Topics

🛒 Get This Book

Buy on Amazon

Buy on Amazon Related Books

Book Discussion

Share your thoughts and opinions on this book and exchange insights with other readers

Join the Discussion

Share your thoughts and opinions on this book and exchange insights with other readers

Loading comments...