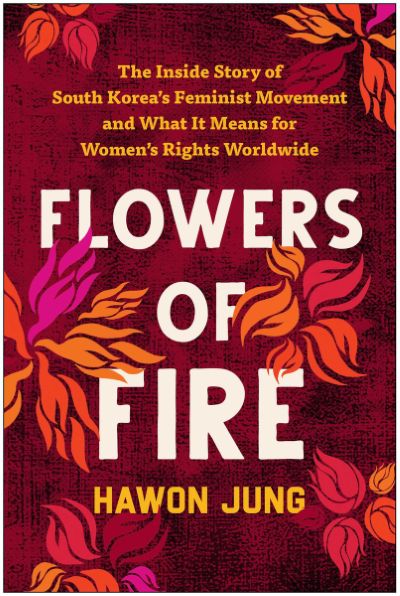

Flowers of Fire: The Inside Story of South Korea's Feminist Movement and What It Means for Women's Rights Worldwide

Former AFP Seoul correspondent Hawon Jung provides a firsthand account from the frontlines of South Korea's feminist movement, documenting how tens of thousands of Korean women sparked a MeToo wave, ended abortion bans, fought spycam crimes, and shattered Western stereotypes of 'docile' Asian women. Named one of The Economist's Best Books of 2023.

📝 Book Review

When the global MeToo movement erupted in 2017, Western media spotlights focused primarily on Hollywood, Wall Street, and Silicon Valley. However, across the Pacific in South Korea, an equally intense and even more thorough feminist revolution was unfolding—thousands of women took to the streets, challenging deeply entrenched patriarchal systems, overturning decades-old abortion bans, bringing down powerful men including presidential candidates, and launching a nationwide war against ubiquitous spycam crimes. The intensity, organizational capacity, and concrete achievements of this movement far exceeded Western observers’ imagination. Yet Korean feminists’ voices have long been marginalized in global conversations about gender equality, their stories largely unknown to the Western world. Hawon Jung’s “Flowers of Fire” aims to change this, bringing this groundbreaking movement into global view.

Hawon Jung is ideally positioned to tell this story. As a former Seoul correspondent for AFP, she has over a decade of reporting experience on Korea and the Korean Peninsula. Born and raised in South Korea, she earned a Master’s degree in journalism from the University of Missouri before returning home to become an international wire service reporter. During her tenure at AFP, she witnessed and reported on major events including the 2011 death of North Korean leader Kim Jong Il, his son Kim Jong Un’s succession, South Korea’s presidential impeachment, and K-pop’s rise on the world stage. But her proudest work is her coverage of South Korea’s MeToo movement—reporting that was shortlisted for the 2019 Society of Publishers in Asia Awards for Editorial Excellence. Her commentary and analysis have appeared in The New York Times, Al Jazeera, BBC, and other international media. She currently divides her time between South Korea and Germany, continuing to focus on and write about women’s rights issues.

The title “Flowers of Fire” itself is a powerful metaphor countering Western stereotypes of Asian women. For too long, Asian women in Western imagination have been portrayed as docile, delicate, submissive “flowers”—whether the colonial-era “Madame Butterfly” image or contemporary pop culture’s “cute girl” stereotypes. Jung wants to tell the world: Korean women are not delicate flowers; they are flames—burning, fighting, impossible to ignore. The title simultaneously evokes the radical and combative nature of the Korean feminist movement itself—they are not requesting equality but demanding it, not waiting for handouts but seizing rights.

The book employs a literary journalism format, interweaving macro social movements with micro personal stories. Jung not only analyzes policies, laws, and statistics but, more importantly, lets readers hear movement participants’ voices, see their faces, understand their fears, anger, courage, and victories. Key figures the book follows include: the elite prosecutor who ignited Korea’s MeToo movement, risking career destruction to publicly accuse her superior of sexual harassment; young women activists who led the anti-spycam movement, inventing new protest strategies to force authorities to take tech-based sexual violence seriously; and women who stood up to share their stories in the abortion rights struggle, breaking social taboos to fight for bodily autonomy for all women.

The catalyst for Korea’s MeToo movement was January 2018, when 29-year-old prosecutor Seo Ji-hyun publicly accused senior prosecutor Ahn Tae-geun of sexual harassment on live television. This was unprecedented in Korea—a junior female prosecutor publicly challenging a male superior with far greater power in a hierarchical, male-dominated judicial system. Seo knew she might destroy her career, even face defamation lawsuits (in Korea, sexual harassment accusers can still be sued for “damaging reputation” even if allegations are true). But she chose to speak out anyway, believing that if even she—highly educated, legally knowledgeable, working in an elite institution—couldn’t obtain justice, what hope did more vulnerable women have?

Seo Ji-hyun’s courageous action was like a spark igniting dry tinder. In the following weeks and months, thousands of Korean women came forward with their own MeToo stories—actors, writers, academics, athletes, ordinary office workers, women from all social strata began breaking silence. Their stories revealed the pervasiveness and systematic nature of gender-based violence in Korean society: workplace sexual harassment treated as normal, victims told to “understand” and “tolerate”; university professors exploiting power relationships to sexually assault female students, schools choosing cover-ups over investigations; cultural “masters” sexually exploiting young women, the industry condoning it in the name of “art.”

But the Korean MeToo movement’s distinctiveness lies not only in exposing abuse but in its determination to demand accountability and its concrete achievements. Multiple high-level men—including a former provincial governor, famous poets, theater directors, film directors—were forced to resign and face legal investigations due to sexual violence allegations, some ultimately convicted. More importantly, the movement drove institutional reforms: sexual harassment laws were strengthened, workplaces required to establish reporting mechanisms, legal protections for victims improved. None of this was government largesse but won through collective action.

Parallel to the MeToo movement was a massive protest against “molka” (spycam) crimes. In Korea, secret filming and illegal distribution of women’s intimate images is a rampant problem—hidden cameras everywhere in public restrooms, changing rooms, subways, hotels; ex-boyfriends, colleagues, strangers uploading women’s intimate images to porn sites. Victims numbered in the tens of thousands, yet police and judicial response was extremely slow. More infuriating, when perpetrators were male and victims female, police often dismissed cases claiming “it’s hard to find suspects”; but in rare cases when perpetrators were female and “victims” were male public figures, police solved cases within hours. This blatant double standard enraged Korean women.

From May to October 2018, for six consecutive months, tens of thousands of women gathered every month at Seoul’s Gwanghwamun Square, holding signs reading “My Life Is Not Your Porn,” demanding police and judicial systems treat spycam cases equally, demanding tech companies take responsibility for platform oversight, demanding society take tech-based sexual violence seriously. The scale of these protests was staggering—some rallies exceeded 70,000 participants, making them among the largest women’s protests in Korean history. Jung meticulously documents these protests’ organizational process: how young women activists used social media to mobilize participants, designed slogans and chants, negotiated with police, responded to anti-feminist backlash, handled internal disagreements.

This movement achieved concrete results. The government established special spycam crime investigation units, installed monitoring equipment in public restrooms, online platforms strengthened review and removal of illegal sexual content. More importantly, societal perception of this issue fundamentally shifted—spycam crimes were no longer seen as “boys’ pranks” or “harmless jokes” but recognized as serious sexual violence. Victims were no longer expected to maintain silence and shame but encouraged to report and seek support.

The third major battleground was abortion rights. Korea banned abortion starting in 1953, criminalizing it with potential imprisonment for both doctors and pregnant women. Though this law was loosely enforced in practice—tens of thousands of abortions still occurred annually—its very existence fundamentally denied women’s bodily autonomy and left women seeking abortions extremely vulnerable: unable to access safe, legal medical services, forced to proceed secretly, unable to seek help if complications arose, potentially facing blackmail and exploitation.

In 2019, Korea’s Constitutional Court ruled the abortion ban unconstitutional, requiring the National Assembly to revise the law by end of 2020. This historic victory didn’t fall from the sky but resulted from decades of feminist movement accumulation, more directly from recent years of young women’s radical action. Jung documents the stories of women who drove this change: women who publicly shared their abortion experiences, risking social shame and legal consequences to break taboos, transforming abortion from an unspeakable “sin” into a public health issue requiring discussion; feminist lawyers and activists pursuing legal challenges, filing lawsuits repeatedly until final victory; young women protesting in the streets wearing black, holding coat hangers (symbolizing unsafe abortion), demanding “My Body My Choice.”

Jung particularly emphasizes innovative strategies and organizational forms women adopted in these movements. Unlike traditional hierarchical social movements, young Korean feminists extensively used social media and digital tools to organize and mobilize. They shared information, coordinated actions, provided emotional support on Twitter, Instagram, and women-only online forums. They developed new protest forms: for example, in anti-spycam protests, they mimicked police rapid response to male victim cases, using megaphones to shout “Women are people too,” satirizing police double standards. They also learned how to protect themselves from online harassment and real-world retaliation: using pseudonyms, encrypted communications, watching out for each other.

But this book is not merely a celebration of victories; it honestly documents challenges and internal tensions facing the Korean feminist movement. Anti-feminist backlash is fierce: the internet filled with hate speech and death threats against feminists; some men organized, claiming men are the “real victims,” accusing feminism of “gender war”; far-right politicians exploited gender issues for political mobilization. In 2022, conservative candidate Yoon Suk-yeol won the presidency, one of his campaign strategies catering to young men’s discontent with feminism, promising to abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality. This reveals the difficulty and reversals on the path to gender equality.

Internal divisions also exist. Most prominent are debates around transgender rights. Some radical feminists argue transgender women should not be included in women’s spaces and movements because their physiological and socialization experiences differ from cisgender women. This position led to intense internal conflict, with some transgender women and their allies leaving certain feminist organizations. Jung doesn’t simply take sides but presents different perspectives and reflects on this controversy’s impact on movement solidarity and effectiveness.

The book also explores class and generational divisions. Young, educated urban women are often movement mainstays, but their demands and strategies don’t necessarily align with realities and needs of rural women, elderly women, working-class women. The MeToo movement focused mainly on white-collar workplaces and cultural sectors, while pervasive sexual harassment in blue-collar industries like factories, restaurants, and care work received less attention. The abortion rights movement emphasizes “choice,” but for many poor women, the issue isn’t just legal ability to choose abortion but whether they can afford safe abortion services and obtain sufficient social support to raise children. Building a movement truly representing all women remains an unfinished task.

Jung situates the Korean experience within global feminist movement contexts, exploring its significance for other parts of the world. She notes many problems Korean women face—sexual violence, tech-based sexual exploitation, reproductive control, gender bias in legal systems, victims questioned while perpetrators sympathized with—exist worldwide. Korean women’s struggle strategies and achievements can provide inspiration and encouragement for women in other countries. Simultaneously, she critiques limitations of Western feminist discourse: it often assumes the West is progressive and the East backward, Western women “rescuing” Eastern women, while ignoring non-Western women’s agency, creativity, and unique contributions.

In fact, in some aspects, the Korean feminist movement is more radical, better organized, and more effective than Western counterparts. Korean women aren’t passively receiving Western feminist thought “imports” but developing unique theories and practices based on their own history and reality. For example, the “escape the corset” movement—young women refusing makeup, refusing dating/marriage, refusing childbearing—protests consumerism’s exploitation of women’s bodies, compulsory motherhood, and corrupt gender systems. This radical refusal strategy is less common in the West; it challenges liberal feminism’s emphasis on “choice,” suggesting that in profoundly unequal societies, sometimes refusal to participate is itself political action.

“Flowers of Fire” is also profound analysis of Korean modern history and social structure. Jung traces historical roots of Korean patriarchy: Confucian cultural tradition’s devaluation of women, violence against women’s bodies during colonial and war periods (including the “comfort women” system), exploitation of women’s labor during rapid industrialization, military dictatorship’s suppression of all dissent (including early feminist movements). She also analyzes contradictions in contemporary Korean society: it’s one of the world’s most economically developed countries with vibrant democratic politics and popular culture, yet simultaneously one of the most gender-unequal developed nations—huge gender wage gaps, extremely low women’s political representation, pervasive violence against women.

This contradiction partly stems from Korea’s particular modernization model: rapid economic development under authoritarian government, which brought material prosperity but also reinforced hierarchical and paternalistic culture. Chaebol-dominated economic structure concentrates power and resources, while issues like gender equality and labor rights were long viewed as obstacles to development. Only after 1987 democratization did social movements gain greater space, and the feminist movement truly emerge. But even under democratic systems, deep cultural and structural gender inequality stubbornly persists—precisely why young women have become so radical and angry in recent years: the promises of democracy and development haven’t brought them genuine equality.

Jung’s writing style combines journalistic accuracy with literary narrative’s emotional power. Her sentences are clear, forceful, full of concrete details and vivid scenes. Readers can feel the heat and tension of protest sites, hear the trembling and firmness in interviewees’ voices, understand movement participants’ complex emotions—the interweaving of fear and courage, anger and hope, exhaustion and persistence. She also doesn’t avoid the complexity her dual identity as journalist and Korean woman brings: she’s both observer and insider, must maintain journalistic objectivity yet cannot deny personal emotional involvement. This honest self-reflection adds authenticity and depth to the narrative.

This book holds special significance for Chinese readers. Though China and Korea differ greatly in history, political systems, and social culture, women in both countries face strikingly similar problems: persistent influence of patriarchal culture, gender role confusion brought by rapid modernization, workplace gender discrimination and sexual harassment, proliferation of tech-based sexual violence, struggles over reproductive control and bodily autonomy, stigmatization and attacks feminists face. Korean women’s resistance experiences—how they organize, speak out, face suppression, achieve victories—can provide inspiration and reference for Chinese women.

Simultaneously, this book reminds us that feminism is not a Western monopoly; East Asian women have their own voices, their own agendas, their own strategies. For too long, global feminist discourse has been dominated by the Anglophone world, with non-Western women’s experiences and theories often marginalized or reduced to “cultural specificity.” “Flowers of Fire,” through detailed, in-depth presentation of the Korean feminist movement, challenges this center-periphery power structure, insisting Korean women’s stories matter not only to Korea but to the entire world.

At the book’s conclusion, Jung returns to the title’s metaphor: flowers and fire. Flowers seem fragile yet are resilient, able to grow in the harshest environments; fire seems destructive yet purifies and regenerates. Korean feminists are both flowers and fire—they grow despite patriarchal oppression and with their fury burn down old orders, clearing space for new worlds to be born. This is not only Korean women’s story but the story of women worldwide. Everywhere, women resist, survive, bloom, and burn in various ways.

“Flowers of Fire” is an important, timely, inspiring book. It shows us that genuine social change is not top-down beneficence but bottom-up struggle; gender equality won’t arrive automatically but requires the courage and sacrifice of generation after generation of women; the global feminist movement needs to listen to and learn from the voices and experiences of women from different regions and cultures. For anyone concerned with gender justice, social movements, and contemporary Korea, this book is essential reading. And for all women living, struggling, persisting under patriarchy, this book is a reminder: we are not isolated, our struggles are connected, we are not delicate flowers—we are flames.

Book Info

Related Topics

🛒 Get This Book

Buy on Amazon

Buy on Amazon Related Books

Book Discussion

Share your thoughts and opinions on this book and exchange insights with other readers

Join the Discussion

Share your thoughts and opinions on this book and exchange insights with other readers

Loading comments...