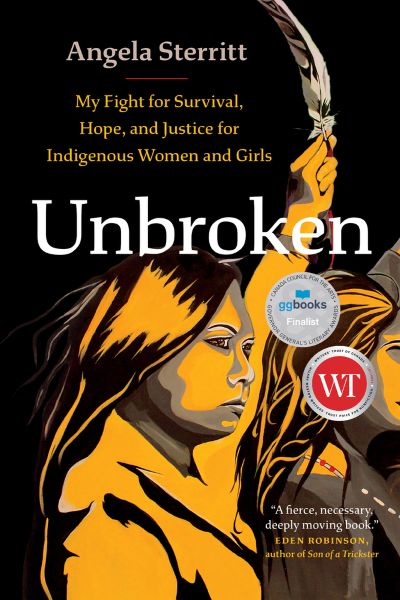

Unbroken: My Fight for Survival, Hope, and Justice for Indigenous Women and Girls

An extraordinary work of memoir and investigative journalism by award-winning Gitxsan journalist Angela Sterritt who survived life on the streets. Combining personal narrative with in-depth investigation into Canada's missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG), this book reveals how colonialism and racism created a society where Indigenous women's lives are ignored and devalued, while proving that Indigenous women's strength and brilliance is unbroken.

📝 Book Review

In Canada’s history, there is a heartbreaking reality: thousands of Indigenous women and girls have gone missing or been murdered, their lives ignored by mainstream society, their stories marginalized, their justice delayed or denied. This is not accidental tragedy but the result of systemic violence created by colonialism and racism—a society that views Indigenous women as disposable, unworthy of protection, unworthy of justice. As a Gitxsan woman who survived life on the streets and is now an award-winning journalist and author, Angela Sterritt has unique perspective and moral authority to tell this story. In her 2021 book Unbroken: My Fight for Survival, Hope, and Justice for Indigenous Women and Girls, she combines personal memoir with investigative reporting to create a work that is simultaneously deeply personal and politically radical—showing how she survived in the darkest places, how her community faces unimaginable loss, and why Indigenous women’s strength, resilience, and brilliance is unbroken.

Angela Sterritt is an award-winning investigative journalist, TV/radio/podcast host, and national bestselling author. She is from the Wilps Wii’k’aax of the Gitanmaax community within the Gitxsan Nation on her father’s side and from Bell Island, Newfoundland, on her mother’s side. She worked as a television, radio, and digital journalist at CBC for over a decade, starting as an on-air researcher in Prince George in 2003 and now based in Vancouver. She won the Best Local Reporter award at the Canadian Screen Awards for her original story about an Indigenous man and his granddaughter wrongfully handcuffed while trying to open a bank account, and also won a national Radio Television Digital News Association award for the same reporting. In 2017, she received the Investigative Award of the Year from Canadian Journalists for Free Expression for CBC’s coverage of missing and murdered Indigenous women. She hosted the award-winning CBC original podcast Land Back, investigating land theft and land reclamation in Canada. Published by Greystone Books in September 2021, Unbroken quickly became a national bestseller and was nominated for the Governor General’s Literary Awards (one of Canada’s oldest and most prestigious literary prizes) and the Hilary Weston Writers’ Trust Award for Best Non-Fiction Book in Canada.

Unbroken is a dual-narrative book: on one hand, Sterritt’s personal memoir telling her journey as a Gitxsan teenager surviving on the streets, finding her place, and ultimately becoming a journalist and advocate; on the other hand, her investigative reporting into cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in Canada (commonly abbreviated as MMIWG). These two narrative threads weave together, illuminating each other and revealing the profound connection between personal and political.

Sterritt grew up steeped in Gitxsan culture, immersed in her ancestors’ stories: grandparents who carried bentwood boxes of berries, hunted and trapped, and later fought for rights and title to that land. These stories gave her a sense of identity, belonging, and connection to land and community. But as a vulnerable young woman, kicked out of the family home and living on the street, Sterritt inhabited places that today are infamous for being communities where women have gone missing or been murdered: Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and, later on, Northern BC’s Highway of Tears.

Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside is one of Canada’s poorest postal codes, known for high rates of homelessness, drug use, sex work, and Indigenous residents. It is also where dozens of women—primarily Indigenous women—went missing or were murdered, many at the hands of serial killer Robert Pickton. The Highway of Tears is a section of Highway 16 in Northern British Columbia where at least 40 women (primarily Indigenous women) have gone missing or been murdered since the 1970s. These places are not just geographic locations; they are symbols representing sites of colonial violence, poverty, marginalization, and abandonment where Indigenous women’s lives are treated as disposable.

Sterritt lived in these places as a teenager. She faced darkness: she experienced violence from partners and strangers, saw friends and community members die or go missing. She lived in group homes, single-room occupancy hotels (SROs), on the street. She struggled with poverty, homelessness, trauma, substance use. She could have become another statistic, another missing Indigenous girl not truly searched for because society viewed her as unimportant.

But Sterritt survived. She wrote in her journal to help her survive and find her place in the world—documenting her experiences, her feelings, her hopes and fears. Writing became a tool not only for survival but for witnessing, processing trauma, and insisting on her value and humanity. She navigated the street, group homes, and SROs to finally find her place in journalism and academic excellence at university, relying entirely on her own strength, resilience, and creativity along with the support of her ancestors and community.

Sterritt is honest about how she survived. She does not romanticize her experiences or portray herself as a flawless hero. She acknowledges the difficult choices she made, the dangerous situations she experienced, the trauma she carried. She also acknowledges those who supported her—community members, mentors, friends—and the strength and guidance of her ancestors. Her survival was not a solo achievement but a combination of her resilience, her community’s support, and a degree of luck.

As a journalist, Sterritt now investigates cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. “She could have been me,” she acknowledges today, and her empathy for victims, survivors, and families drives her present-day investigations. She reports on many cases, providing names, faces, and stories for women who have been ignored or treated callously by mainstream media. She interviews family members who have been searching for missing loved ones for years, often without adequate support from police or government. She exposes how racism, sexism, and classism shape whose disappearance or death is valued, who gets justice.

Sterritt’s investigations reveal disturbing patterns. When white women or middle-class women go missing, media coverage is often extensive and sympathetic, police investigations active, public attention high. But when Indigenous women go missing, the response is often cold and neglectful. Media may not report at all, or they may use dehumanizing language suggesting victims were “at risk” or somehow responsible for their fate. Police may not take missing persons reports seriously, assuming women just “ran away” or were not worth searching for. The public may not care or know. This differential treatment is not accidental; it is systematic manifestation of racism and sexism viewing Indigenous women as less valuable, less human, unworthy of protection or justice.

Sterritt traces the historical roots of this dehumanization. Colonialism is not just a past historical event; it is an ongoing process continuing to shape Indigenous peoples’ lives. When European colonizers arrived in what is now called Canada, they brought ideologies viewing Indigenous people as less than human, savage, needing to be “civilized” or eliminated. They seized land through violence, forced relocations, disease, war. They established the residential school system, forcibly removing Indigenous children from families attempting to “kill the Indian, save the man”—eliminate Indigenous culture, language, identity. These schools were sites of trauma, abuse, neglect, and death; many children never came home.

The residential schools’ impacts are intergenerational. Those who survived the schools—including some of Sterritt’s family members—often returned with deep trauma, lost cultural connections, broken family relationships. This trauma passes to the next generation, manifesting as substance use, domestic violence, mental health issues, poverty. Colonialism created conditions making Indigenous communities vulnerable—poverty, marginalization, lack of access to education/employment/healthcare—then blames Indigenous people for the results of these conditions.

For Indigenous women, this colonial violence is gendered. Colonizers not only viewed Indigenous men as threats or inferior but sexualized, objectified, and dehumanized Indigenous women. Indigenous women were portrayed as sexually available, exotic, “easy”—stereotypes justifying violence against them and enabling perpetrators to escape with impunity. Simultaneously, Indigenous women were stripped of power, authority, and respected roles they traditionally held in many Indigenous communities. Many Indigenous societies were matrilineal or at least relatively gender-egalitarian pre-colonially, with women serving as leaders, spiritual guides, decision-makers. But colonizers imposed European patriarchal structures, giving power to men, marginalizing women, undermining Indigenous gender systems.

Today, Indigenous women face disproportionately high rates of violence. Statistics in Canada are staggering: although Indigenous women represent only 4% of Canada’s female population, they account for 16% of female homicide victims. Indigenous women are more than three times as likely to experience violence as non-Indigenous women. Cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls number in the thousands—the exact number unknown because many cases are never reported or investigated. This is not because violence is inherent within Indigenous communities; it is because colonialism created conditions where violence thrives and because violence against Indigenous women has been normalized, ignored, and gone unpunished.

Sterritt also explores intersectionality—how gender intersects with race, class, sexuality, and other identities to create unique patterns of vulnerability and oppression. Not all Indigenous women experience violence or marginalization in the same way. Poor Indigenous women, sex workers, homeless women, women with substance use issues, transgender Indigenous women face particularly high risk of violence because of multiple intersecting marginalized identities. Sterritt’s own experience—as a homeless young Indigenous woman living in the Downtown Eastside and near the Highway of Tears—placed her at high risk for violence. She survived, but many others in similar situations did not.

One of the book’s most powerful aspects is how Sterritt humanizes the missing and murdered women. She does not reduce them to statistics or abstract victims; she tells their stories, shares their names, shows them as full, complex people—daughters, sisters, mothers, friends, community members. She interviews their loved ones who continue to mourn, continue seeking justice, continue remembering. She shows how each disappearance or murder is violence not only against the victim herself but against her family, her community, her nation—robbing them of knowledge, culture, and futures.

Sterritt also exposes institutional failures: police who failed to investigate seriously, often blaming victims or ignoring families’ concerns; governments that failed to provide adequate resources for violence prevention or survivor support; media that failed to adequately cover cases or perpetuated harmful stereotypes; justice systems that failed to hold perpetrators accountable or provide justice for victims and families. These failures are not isolated mistakes; they are systemic issues reflecting deep-rooted racism and sexism.

In 2016, after decades of pressure from advocates, survivors, and families, the Canadian government launched the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (commonly called the MMIWG Inquiry). The inquiry ran for three years, heard from over 2,380 witnesses, reviewed thousands of pages of documents, and produced a final report concluding that violence against Indigenous women constitutes “genocide”—deliberate destruction of a group through systematic violence targeting that specific group.

The report issued 231 “Calls for Justice”—recommendations for government, institutions, and all Canadians to take action to end violence and achieve justice. These include: reforming policing to ensure Indigenous women’s cases are taken seriously; increasing funding for support services, housing, and mental health resources in Indigenous communities; reforming the justice system to better serve Indigenous victims and survivors; addressing root causes of poverty, discrimination, and marginalization; respecting Indigenous rights and self-determination; educating the public about MMIWG and colonial history; ensuring media report on Indigenous women in respectful and accurate ways.

But Sterritt and many advocates note that progress since the inquiry report has been slow and incomplete. Many Calls for Justice remain unimplemented. Violence continues. Indigenous women still go missing and are murdered. Sterritt demands accountability—not only from government and institutions but also from media and the public. She exposes ongoing racism in media coverage of Indigenous issues, including use of stereotypes, failure to respectfully consult Indigenous communities, or hire Indigenous journalists. She calls for structural change, not just symbolic gestures or surface reforms.

But Unbroken is ultimately a book of hope and resilience. Sterritt’s survival itself is an act of resistance and triumph. She refused to be defined or defeated by colonialism and racism. She found her path in journalism and advocacy, using her voice and platform to speak for those who have been silenced. She reconnected with her culture, her community, her ancestors. She built a life of abundance, joy, and purpose.

Sterritt also celebrates Indigenous women and girls’ strength and brilliance. Despite facing unimaginable violence and oppression, Indigenous women continue to survive, resist, create, and thrive. They are leaders, activists, artists, scholars, mothers, grandmothers, knowledge keepers. They keep culture and language alive. They fight for their communities and their lands. They build coalitions and movements. They heal and support each other. Their strength is unbroken—as the book’s title suggests.

From a feminist theory perspective, Unbroken is a powerful expression of Indigenous feminism and decolonial feminism. It demonstrates how gender oppression is inseparably linked to colonialism and racism—that one cannot understand Indigenous women’s experiences without understanding colonial history and ongoing structural violence. It embodies intersectional feminist principles, recognizing how multiple identities intersect to create unique forms of oppression and resilience. It is rooted in Indigenous epistemologies and methodologies, centering Indigenous knowledge, stories, and community relationships.

Sterritt’s approach—combining personal narrative with investigative reporting—is also powerful. She does not present herself as an objective, detached journalist but places her own experiences, her perspective, her commitments at the forefront. She shows how journalists can be rooted in the communities they report on, driven by personal experiences and values, using their privilege and platform to fight for justice. This challenges mainstream journalism norms that often value objectivity and detachment, separating journalists from their subjects, pretending no bias or stance exists.

For non-Indigenous readers, Unbroken is a necessary education and challenge. It requires us to confront the ongoing reality of colonialism and its impacts on Indigenous peoples. It requires us to acknowledge our complicity in perpetuating injustice—through our silence, our ignorance, our benefit from colonial systems. It requires us to listen to Indigenous voices, respect Indigenous sovereignty, support Indigenous movements for justice. It requires us not only to sympathize with victims and survivors but to take action to change the systems making violence possible.

For Indigenous readers, particularly Indigenous women and girls, Unbroken may be a source of validation, recognition, and inspiration. It reflects their experiences, witnesses their pain, celebrates their strength. It shows they are not alone, their struggles are collective, their resilience is powerful. It offers a model for survival, healing, and thriving.

Angela Sterritt’s Unbroken: My Fight for Survival, Hope, and Justice for Indigenous Women and Girls is a profoundly powerful, brave, and necessary work. It is simultaneously a deeply personal memoir and rigorous investigative reporting, both an indictment of colonial violence and a celebration of Indigenous resilience. For anyone wanting to understand Canada’s crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, the ongoing impacts of colonialism, or simply the extraordinary story of a woman who refused to be broken, this book is essential reading. It reminds us that Indigenous women’s lives matter, their stories must be told, their justice must be achieved. As Sterritt writes: “We are unbroken. We continue. And together, we can build lives of joy and abundance.” This is an invitation to all of us—to listen, to learn, to support, and to fight for justice and freedom for all Indigenous women and girls.

Book Info

Related Topics

🛒 Get This Book

Buy on Amazon

Buy on Amazon Related Books

Book Discussion

Share your thoughts and opinions on this book and exchange insights with other readers

Join the Discussion

Share your thoughts and opinions on this book and exchange insights with other readers

Loading comments...