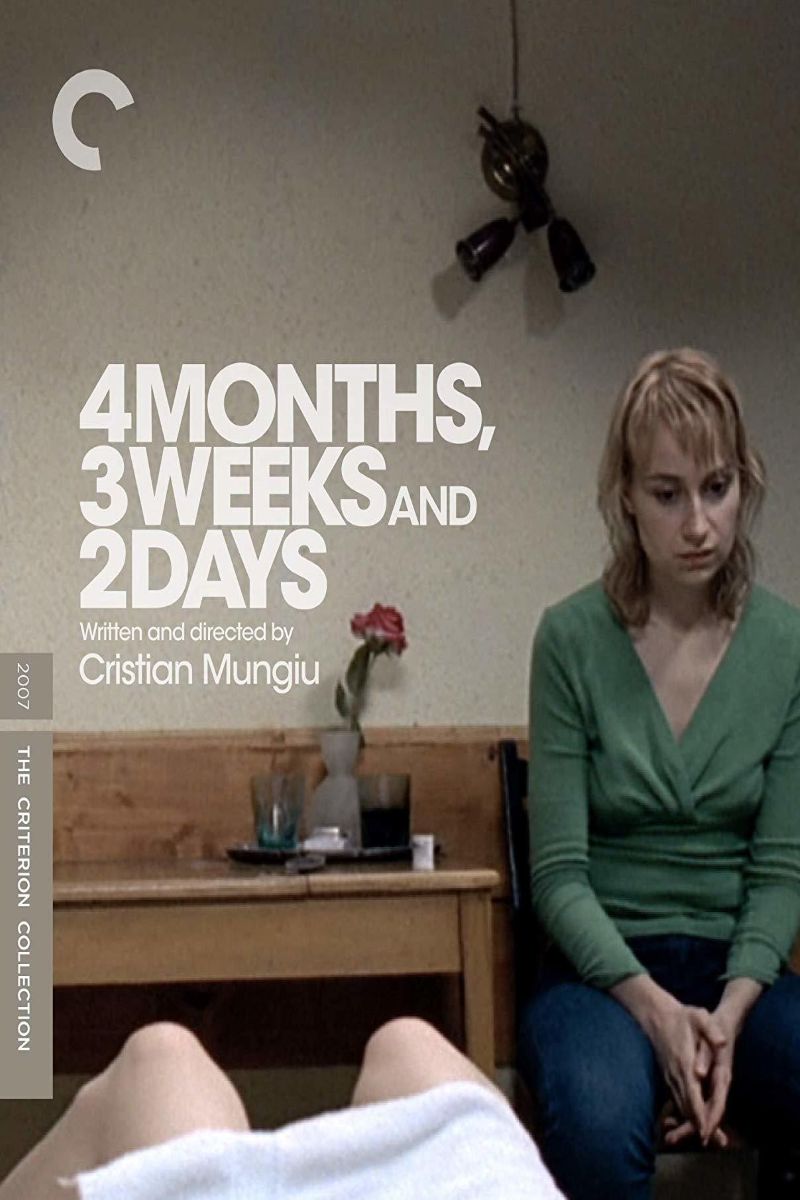

4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days

4 luni, 3 săptămâni și 2 zile

In 1987 Romania under Ceaușescu's dictatorship, college roommate Otilia helps pregnant Găbița seek an illegal abortion. This harsh and brutal realist masterpiece reveals the state's control over women's bodies and women's brave resistance for reproductive autonomy within the span of one night.

Cast

Related Topics

🎥 Film Analysis & Review

“4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days” stands as one of the most important works in feminist cinema history, with director Cristian Mungiu employing his austere yet precise realist style to create an epic indictment of reproductive autonomy. This film serves not only as a powerful critique of Ceaușescu’s authoritarian regime but as a profound reflection on women’s global struggle for bodily autonomy. Through events occurring within 24 hours, the film reveals the devastating consequences when states attempt to control women’s bodies.

The political background is crucial to understanding the film’s significance. In 1966, Ceaușescu’s government enacted Decree 770, completely banning abortion with the goal of increasing Romania’s population from 23 million to 30 million. This decree imposed strict reproductive control on women under 45 who had fewer than five children, treating women’s wombs as state assets. Under this policy, thousands of women died from illegal abortions, orphanages overflowed with uncared-for children, and society bore enormous humanitarian disasters.

From feminist perspectives, the film’s portrayal of friendship and solidarity carries profound political implications. Otilia’s (Anamaria Marinca) selfless assistance to Găbița (Laura Vasiliu) represents not merely personal emotional expression but exemplifies female mutual support under patriarchal oppression. This female solidarity transcends personal interests, embodying collective resistance spirit when women face common threats.

The film’s depiction of the illegal abortion process is both brutal and necessary. Mungiu refuses to romanticize or simplify this process, instead presenting the dangers and humiliation women face when lacking legal protection with disturbing authenticity. The character of Mr. Bebe (Vlad Ivanov) embodies the complexity of illegal medical service providers—simultaneously savior and exploiter, reflecting the distorted nature of power relations in underground economies.

From reproductive autonomy perspectives, the film raises fundamental questions about women’s bodily ownership. When states claim control over women’s reproductive capacity, women’s basic human rights are stripped away. Găbița’s pregnancy isn’t her choice but the result of systematic oppression—lack of contraceptive access, sex education, and safe medical services. Her situation represents countless women who lost reproductive choice under authoritarian regimes.

The film’s narrative structure itself carries feminist characteristics. The entire film unfolds almost completely from female perspectives, with male characters existing but remaining marginalized. This narrative choice centers women’s experiences, challenging traditional cinema’s male-dominated storytelling patterns. Otilia’s perspective allows audiences to deeply experience women’s psychological states and moral choices during crisis moments.

The film’s portrayal of class differences also carries important significance. Otilia and Găbița’s economic difficulties make them more vulnerable to exploitation. They must borrow money, take risks, and even accept sexual exploitation to obtain medical services. This portrayal reveals how economic inequality exacerbates gender oppression, forcing poor women to face greater risks and costs when seeking reproductive choices.

The film’s use of time creates a tense and oppressive atmosphere, reflecting women’s psychological experience during crisis moments. The extended real-time narrative allows audiences to feel the agony of waiting, accumulating fear, and time’s urgency. This temporal sense serves not merely as artistic technique but as accurate simulation of psychological pressure women endure when seeking abortion.

The film’s critique of bureaucratic systems reveals how authoritarian regimes control personal lives through tedious procedures and surveillance. From hotel registration to hospital examinations, every detail reflects state penetration into private life. This omnipresent surveillance makes women’s choices more difficult and dangerous, embodying authoritarian systems’ comprehensive suppression of personal freedom.

From psychological perspectives, the film demonstrates how trauma and guilt affect women’s mental health. Găbița’s numbness and detachment throughout the process reflect psychological defense mechanisms she adopts to cope with extreme pressure. This portrayal avoids romanticizing victims while honestly presenting trauma’s impact on personality.

The film’s treatment of motherhood concepts deserves particular attention. By refusing to become a mother, Găbița actually rejects the identity role the state imposes upon her. This refusal isn’t denial of motherhood but resistance to forced motherhood. The film suggests that genuine motherhood should be based on choice rather than compulsion, love rather than obligation.

The film’s visual style—long takes, fixed camera positions, natural lighting—creates documentary-like authenticity, reinforcing the story’s political and social significance. This aesthetic choice rejects commercial cinema’s sensational techniques, instead conveying profound humanistic concern through plain visual language.

From international feminist perspectives, “4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days” transcends Romania’s specific historical context. In many parts of the world, women still face restrictions on reproductive choices and bodily autonomy deprivation. The film reminds us that struggles for reproductive autonomy are global, requiring continuous attention and action.

The film’s exploration of medical ethics also carries contemporary relevance. Under illegal conditions, medical services often accompany exploitation and risk. Mr. Bebe’s character demonstrates this moral complexity—he provides desperately needed services while exploiting women’s desperate circumstances. This portrayal reminds us that only under legal protection can women obtain safe, dignified medical services.

The film’s treatment of secrecy and silence themes reflects additional burdens women must bear when seeking reproductive choices. Keeping secrets serves not only to avoid legal consequences but also social shame and moral condemnation. This forced silence intensifies women’s isolation, hindering their pursuit of support and assistance.

From generational perspectives, the film demonstrates different attitudes toward this issue among women of different ages. Older women’s silence and younger women’s confusion reflect different experiences and concepts regarding reproductive rights across generations. These generational differences remind us that fighting for women’s rights requires cross-generational inheritance and collective effort.

The film’s ending is filled with openness and uncertainty, reflecting real life’s complexity. There are no simple solutions, no perfect endings, only women’s persistence and resistance in adversity. This realistic treatment avoids cheap sentimentality while leaving space for audience reflection and action.

The film’s exploration of female agency under extreme circumstances demonstrates remarkable complexity. Otilia’s decisions throughout the night—from securing money to negotiating with Mr. Bebe to disposing of the fetus—reveal how women navigate impossible choices with limited options. Her agency isn’t heroic in traditional terms but represents the kind of practical wisdom women develop when existing systems fail them.

The portrayal of male characters in the film is equally significant in its restraint. Men appear as obstacles, threats, or sources of bureaucratic power rather than as saviors or protagonists. This narrative choice reflects the reality that in struggles for reproductive rights, women must primarily rely on each other rather than male intervention or permission.

The film’s treatment of memory and forgetting also carries feminist implications. The way characters attempt to process and move beyond their traumatic experience suggests how women cope with state violence against their bodies. The film doesn’t provide easy closure but acknowledges the ongoing psychological cost of living under oppressive regimes.

From economic feminist perspectives, the film reveals how poverty intersects with reproductive oppression. The women’s need to gather money, their vulnerability to exploitation, and their limited options all demonstrate how class inequality compounds gender-based restrictions. This intersectional analysis strengthens the film’s critique of systemic oppression.

The international success of “4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days” proves feminist cinema’s universal value and artistic power. It’s not merely a film about Romanian history but a work addressing universal female experiences. In today’s world, when reproductive rights still face challenges, this film’s significance becomes even more pronounced.

Ultimately, this film’s value lies in its steadfast defense of women’s dignity and autonomy. It tells us that women’s bodies belong to themselves, and no external force—whether state, religious, or traditional—has the right to decide their reproductive choices. In a world still fighting for true gender equality, “4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days” reminds us that the struggle for women’s rights never becomes outdated because it concerns humanity’s most basic dignity and freedom.

🏆 Awards & Recognition

- • Cannes Film Festival Palme d'Or

- • European Film Award Best Film

- • Los Angeles Film Critics Association Award Best Foreign Language Film

- • London Film Critics Circle Award Best Foreign Language Film

- • Chicago Film Critics Association Award Best Foreign Language Film

⭐ Ratings & Links

Related Recommendations

Comments & Discussion

Discuss this video with other viewers

Join the Discussion

Discuss this video with other viewers

Loading comments...