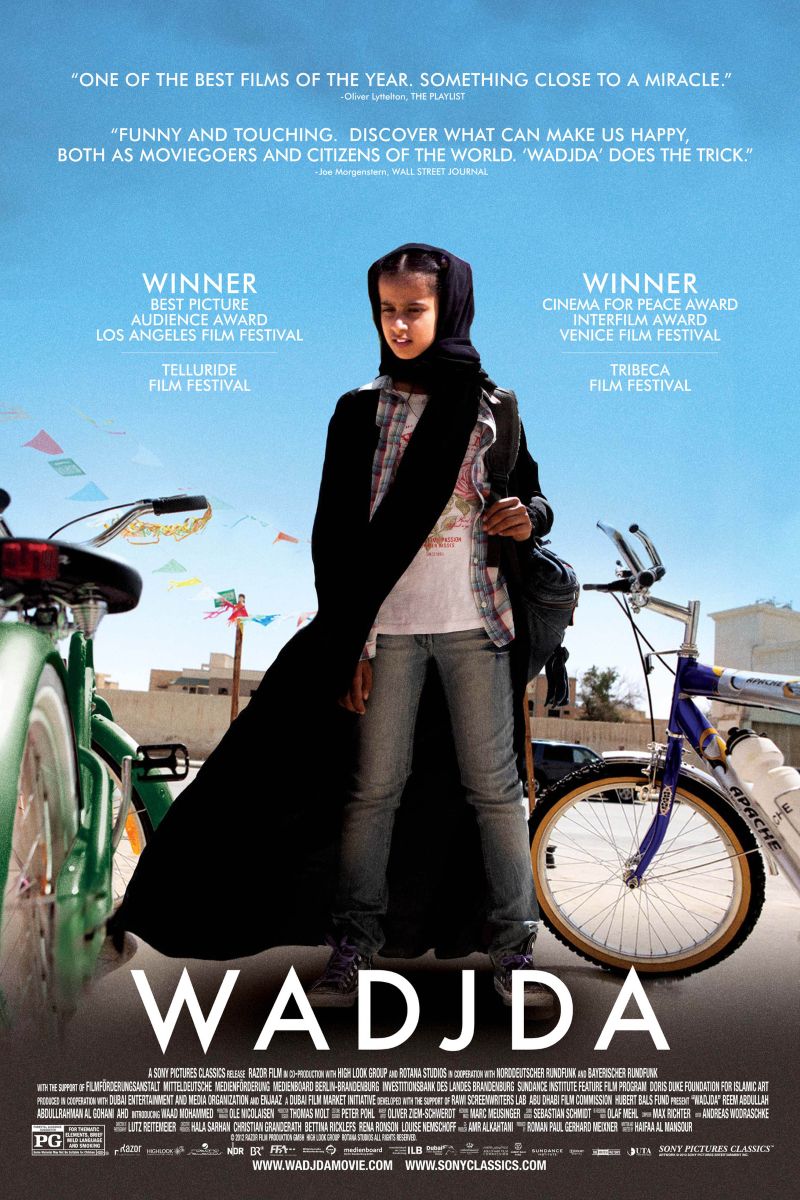

Wadjda

Wadjda

10-year-old Saudi girl Wadjda dreams of owning a green bicycle to race with her male friend Abdullah. This groundbreaking work is the first feature film shot entirely in Saudi Arabia and the first directed by a Saudi woman, exploring complex themes of female freedom, social constraints, and cultural transformation through a girl's desire for a bicycle.

Cast

Related Topics

🎥 Film Analysis & Review

Wadjda stands as a milestone work in Saudi Arabian cinema history, with director Haifaa al-Mansour not only creating the country’s first feature film shot entirely within its borders but also becoming the first Saudi woman to direct a feature film. This seemingly simple coming-of-age story, through 10-year-old girl Wadjda’s (Waad Mohammed) persistent desire for a green bicycle, profoundly explores women’s freedom of movement in Saudi society, conflicts between cultural tradition and modernization, and women’s survival wisdom and resistance strategies under strict gender segregation systems.

From gender norm challenge perspectives, the bicycle becomes a powerful symbolic element in the film. In Saudi traditional culture, women riding bicycles is considered behavior contrary to moral norms, and Wadjda’s desire for a bicycle represents instinctive rebellion against such gender restrictions. Whenever she mentions plans to buy a bicycle, she encounters collective opposition of “Girls can’t ride bicycles!” However, Wadjda’s persistence embodies young women’s courage and creativity in challenging established gender roles.

The film’s contribution to Arab feminism lies in its subtle yet profound critical strategy. Though director al-Mansour denies this is a “feminist film,” every detail of the film permeates deep concern for women’s circumstances. Wadjda’s bicycle dream echoes with the reality that adult women cannot drive, revealing systematic problems of restricted freedom of movement for women in Saudi society. The plot of the mother being trapped at home due to the driver’s willfulness vividly demonstrates the actual impact of such restrictions on women’s daily lives.

From cultural identity perspectives, Wadjda must find balance between traditional expectations and personal desires. She exists in a social environment demanding women be docile and well-behaved, yet possesses a lively, independent nature. The film shows how she seeks creative methods to achieve personal goals without completely violating family and social expectations. Her participation in Quran recitation competitions to earn money for buying a bicycle embodies strategic resistance within restrictive environments.

The theme of family liberation is profoundly embodied through Wadjda’s relationship with her mother. The mother loves her daughter deeply but also worries that her “inappropriate” behavior will bring social consequences. The mother herself faces threats of her husband potentially taking a second wife, and this insecurity makes her more cautiously maintain traditional norms. The film shows how intergenerational women struggle between love and fear, protection and restriction, and how they seek possibilities for mother-daughter solidarity under patriarchal pressure.

From youth rights perspectives, Wadjda represents young people’s struggle for autonomy and expression rights. Adults often restrict children’s choices in the name of “protection,” but Wadjda proves through her actions that young people are capable of understanding social rules and finding space for action within them. Her entrepreneurial spirit—making bracelets for sale, participating in competitions to earn money—demonstrates young women’s agency and creativity.

Religious patriarchy critique in the film is subtle yet powerful. School religious courses emphasize women’s obedience and traditional roles, but Wadjda’s questioning of these teachings embodies new generation challenges to religious interpretation authority. Her excellent performance in the Quran recitation competition proves that piety and independent thinking are not contradictory, and women can seek more expression space within religious frameworks.

From economic empowerment perspectives, Wadjda’s efforts to autonomously earn money through various means embody the importance of women’s economic independence. She makes bracelets, completes school tasks, participates in competitions, all to achieve her economic goals. This economic initiative is especially precious in traditional society, as economic dependence is often the fundamental reason for women’s control.

The complexity of mother-daughter relationships forms the film’s emotional core. Wadjda’s mother is both a bearer of traditional values and a victim of patriarchy. She has both deep love for her daughter and realistic concerns. The film’s final decision of the mother buying a bicycle for her daughter represents a moment when maternal love transcends social fear, also symbolizing understanding and support between female generations.

The filming process itself carries feminist significance. Al-Mansour had to create under gender segregation restrictions, often needing to hide in trucks and direct filming through walkie-talkies. These difficult creative conditions reflect challenges Saudi women face in various fields while also proving female creators’ resilience and creativity.

From visual language perspectives, the film uses many low-angle shots to present Wadjda’s perspective, emphasizing her vulnerability as a child while also showing her curiosity and longing when looking up at the world. The green bicycle in the bicycle shop appears repeatedly in frames, becoming a visual metaphor for hope and dreams.

The film’s portrayal of spatial politics reveals the absurdity of gender segregation systems. Gender-separated areas in schools, gendered spatial arrangements in families, restrictive regulations in public spaces all embody how patriarchy maintains gender hierarchy through spatial control. Wadjda’s crossing of these boundaries—sneaking onto the rooftop, playing with boys—represents challenges to spatial gendering.

From educational perspectives, the film shows two different educational philosophies. Formal school education emphasizes rules and obedience, while Wadjda’s autonomous learning—observation, experimentation, innovation—embodies another learning method. Life skills she learns through personal practice often have more practical value than classroom knowledge.

The film’s treatment of friendship and gender boundaries also deserves attention. Wadjda’s friendship with boy Abdullah must be carefully maintained under social supervision, and this restriction reflects how gender segregation systems affect children’s social development. However, their friendship also shows possibilities for transcending gender prejudice.

From psychological development perspectives, Wadjda’s growth process shows healthy self-consciousness formation. She didn’t abandon her interests and personality due to social pressure but learned to find balance between maintaining self and adapting to environment. This psychological resilience lays foundation for facing greater challenges in her future.

The film’s music design also serves its thematic expression. The fusion of traditional Arab music with modern elements symbolizes possible integration of traditional culture with modern changes. Wadjda’s personal theme music often appears during her most free and happy moments.

From social transformation perspectives, Wadjda represents emerging forces of change in Saudi society. Her story seemed prescient in 2012, foreshadowing major reforms in Saudi society later, including historic changes like women gaining driving rights in 2018.

The film’s portrayal of consumer culture is also worth considering. Wadjda’s desire for a bicycle partially stems from material desire but more deeply represents longing for freedom and equality. She learned to obtain what she wants through legitimate means in consumer society, and this economic participation itself is a form of empowerment.

Ultimately, Wadjda’s value lies in providing an international platform for Arab women’s voices, especially young women’s voices. Through a seemingly simple children’s story, the film successfully brought Saudi society’s gender issues into global dialogue. Wadjda’s victory is not only personal but also symbolic—it foreshadows that the new generation of Arab women’s longing for freedom and equality will eventually be realized. In a region experiencing profound social transformation, this hopeful narrative carries important cultural and political significance.

🏆 Awards & Recognition

- • Venice Film Festival Luigi De Laurentiis Award

- • BAFTA Best Foreign Language Film Nomination

- • Academy Award Best Foreign Language Film Saudi Arabia's First Nomination

- • Arab Film Festival Best Film

⭐ Ratings & Links

Related Recommendations

Comments & Discussion

Discuss this video with other viewers

Join the Discussion

Discuss this video with other viewers

Loading comments...