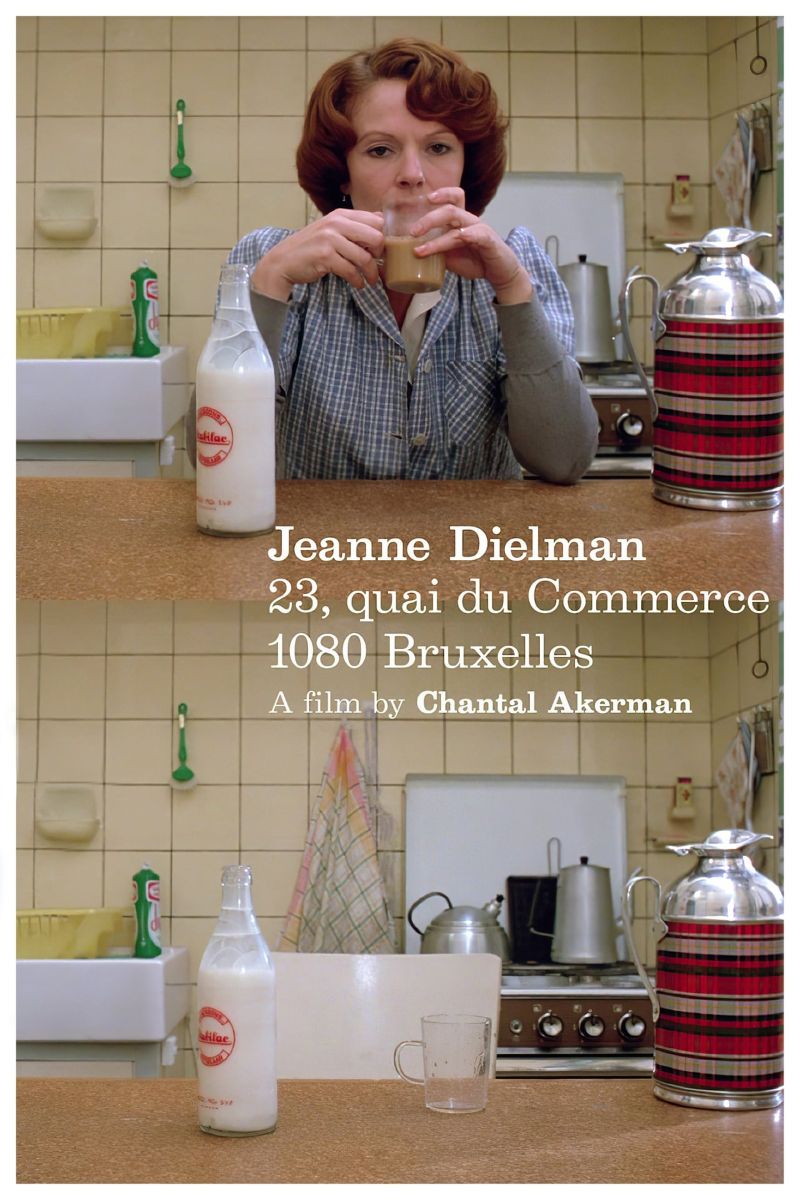

Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quay du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles

Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles

There's no rioting, protesting, or marching for civil rights here. Jeanne Dielman, single mother and sometime sex worker, has a simple life: laundry, dinner, the occasional john. The mundanity of being a housewife is on achingly tedious display for three-plus hours in Chantal Akerman's experimental film. And that's why it's brilliant.

主演

🎥 影评与解读

Chantal Akerman’s “Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles” stands as one of the most radical and influential works in the history of feminist cinema, transforming the simple documentation of domestic routine into a revolutionary statement about women’s labor, time, and existence. This 1975 masterpiece, running over three hours, achieved what few films have dared: it made the invisible visible, elevating the mundane activities of housework to the level of profound cinematic art while simultaneously offering a devastating critique of patriarchal structures that confine women to lives of repetitive, unacknowledged labor.

Revolutionary Form as Feminist Statement

Akerman’s formal approach represents a radical departure from traditional narrative cinema, employing long takes, static camera positions, and real-time documentation of domestic activities to create what amounts to a new cinematic language entirely. The film’s revolutionary nature lies not in what it adds to cinema but in what it removes: the male gaze, narrative urgency, and the assumption that women’s domestic lives are inherently uninteresting or cinematically unworthy.

Each shot is meticulously composed to present Jeanne’s activities—cooking, cleaning, organizing—with the same gravity typically reserved for dramatic action sequences. This formal equality between domestic work and traditionally “important” cinematic subjects represents a fundamental feminist intervention in how we understand what deserves attention and artistic treatment.

The film’s 201-minute runtime becomes a crucial element of its feminist politics. By forcing audiences to experience the actual duration of domestic tasks, Akerman creates empathy through temporal immersion. Viewers must confront their own impatience with these activities, revealing the cultural devaluation of women’s work that typically renders it invisible in artistic representation.

The Architecture of Female Time

“Jeanne Dielman” operates according to what could be called “female time”—cyclical, repetitive, and organized around maintenance rather than progress. This temporal structure directly challenges the linear, goal-oriented narrative logic that dominates mainstream cinema and reflects broader masculine approaches to time and achievement.

Jeanne’s days are structured around routine: preparing meals, serving her teenage son, maintaining the apartment, and receiving male clients for sexual services. This rhythm reveals how women’s time is often not their own but organized around serving others’ needs—their children, their clients, their households. The film’s formal commitment to this temporal reality becomes a form of political solidarity with countless women whose lives follow similar patterns.

The breakdown of routine in the film’s final act gains power precisely because we’ve experienced the weight and regularity of Jeanne’s normal schedule. When small disruptions begin to cascade into larger disruptions, the audience feels the significance because we’ve been immersed in the precise rhythm being disrupted.

Domestic Labor as Economic and Emotional Work

Akerman’s camera reveals domestic work as complex, skilled labor requiring physical stamina, emotional regulation, and precise timing. The film documents not just the visible aspects of housework but the invisible emotional and psychological labor involved in maintaining family stability and comfort.

Jeanne’s preparation of meals becomes a choreographed performance requiring planning, skill, and attention to detail. Her shopping trips reveal the economic calculations underlying household management. Her interactions with her son show the emotional labor involved in maintaining family relationships while suppressing her own needs and desires.

The film’s treatment of Jeanne’s sex work as simply another form of labor—neither sensationalized nor morally condemned—offers a radical perspective on how women’s economic survival often depends on different forms of service to male needs. The matter-of-fact presentation of these afternoon appointments challenges audiences to see sex work as labor rather than moral failing.

The Male Gaze Dismantled

Perhaps no film has more completely eliminated the male gaze from its visual language. Akerman’s camera never objectifies Jeanne, never presents her as spectacle for male viewing pleasure. Instead, the camera observes with the detached but respectful attention of a documentary filmmaker recording important cultural practices.

This visual approach extends to the film’s treatment of sexuality and intimacy. When Jeanne services male clients, the camera remains outside or focuses on peripheral details rather than voyeuristically documenting sexual activity. This choice emphasizes the work aspect of these encounters rather than treating them as opportunities for viewer titillation.

The absence of traditional cinematic glamorization creates space for audiences to see Jeanne as a complete person rather than a collection of roles and functions. We observe her internal life through external behavior, developing understanding through extended observation rather than psychological exposition.

Class and Economic Precarity

The film provides subtle but persistent commentary on women’s economic vulnerability under patriarchal capitalism. Jeanne’s middle-class apartment and lifestyle are maintained through a combination of domestic labor and sex work, revealing how women’s economic stability often depends on serving male needs in various capacities.

Her relationship with money—carefully counting earnings, budgeting for household expenses, calculating costs—shows the economic precision required for survival as a single mother. The film demonstrates how economic marginality shapes every aspect of women’s daily experience without reducing her to a victim of circumstances.

The contrast between Jeanne’s careful financial management and her son’s casual consumption of her labor reveals generational and gendered differences in understanding domestic work’s economic value. Her son receives meals, clean clothes, and domestic comfort without apparent awareness of the work involved in providing these services.

Maternal Labor and Emotional Suppression

Jeanne’s relationship with her teenage son provides one of the film’s most complex explorations of maternal labor. Her interactions reveal the emotional suppression required to maintain the appearance of maternal availability while managing her own psychological and economic pressures.

The film shows how motherhood under patriarchy requires women to function as service providers while suppressing their own emotional needs. Jeanne’s careful attention to her son’s comfort—preparing his preferred foods, maintaining his clothing, providing emotional stability—occurs while her own interior life remains largely unexpressed.

The son’s casual expectation of maternal service, combined with his apparent obliviousness to her work, illustrates how patriarchal family structures reproduce themselves through normalized exploitation of maternal labor. The film neither condemns the son nor excuses the structure but simply documents this dynamic with devastating clarity.

The Breakdown of Performance

The film’s climactic sequence, in which Jeanne’s carefully maintained routines begin to unravel, represents one of cinema’s most powerful depictions of feminine psychological breakdown. Small disruptions—burned potatoes, a missed button, a lamp left burning—cascade into larger ones as Jeanne’s ability to maintain her performance of domestic competence begins to fail.

This breakdown functions as both personal crisis and political metaphor. On the personal level, it shows the psychological cost of suppressing authentic selfhood in service of others’ needs. On the political level, it suggests the inherent instability of systems that depend on women’s unacknowledged labor and emotional suppression.

The film’s shocking conclusion—Jeanne’s violent response to a client—explodes the careful control that has defined her existence. This moment reads not as random violence but as the inevitable result of a system that demands complete self-suppression while providing no outlet for authentic expression or genuine agency.

Influence on Feminist Film Theory

“Jeanne Dielman” became a foundational text for feminist film theory, demonstrating how formal innovation could serve political ends. The film’s approach influenced decades of thinking about alternative cinematic languages and the relationship between form and political content.

The film proved that experimental cinema could address political issues without sacrificing artistic rigor or intellectual complexity. Its success opened spaces for other feminist filmmakers to explore non-traditional narrative structures while maintaining accessibility to engaged audiences.

Contemporary filmmakers including Todd Haynes, Céline Sciamma, and Gus Van Sant have acknowledged the film’s influence on their own approaches to time, character, and narrative structure. The film’s legacy appears in everything from slow cinema to domestic realism to feminist horror.

Recognition and Critical Reevaluation

The film’s 2022 selection as the greatest film of all time by Sight and Sound magazine—the first film directed by a woman to achieve this honor—represents a historic recognition of feminist cinema’s artistic and political importance. This acknowledgment reflects changing critical perspectives that value previously marginalized voices and approaches.

The film’s journey from initial mixed reception to current status as a masterpiece illustrates how feminist art often requires time to find its proper audience and critical context. Early dismissals of the film as “boring” or “pointless” revealed critics’ inability to recognize the radical nature of Akerman’s intervention.

Contemporary Relevance

In an era of renewed attention to domestic labor’s economic value, especially following COVID-19’s illumination of care work’s essential nature, “Jeanne Dielman” feels remarkably prescient. The film’s documentation of household management, emotional labor, and the psychological costs of service work speaks directly to contemporary discussions about women’s unpaid labor.

The film’s treatment of sex work as labor rather than moral issue anticipates current debates about sex workers’ rights and economic agency. Its non-judgmental presentation of Jeanne’s choices provides a model for approaching complex issues around women’s economic survival and bodily autonomy.

Methodological Innovation

Akerman’s approach created new possibilities for representing women’s experiences cinematically. Her use of real time, stationary cameras, and mundane activities demonstrated that women’s daily experiences could sustain artistic attention without requiring dramatic enhancement or male-centered conflict.

The film’s influence extends beyond feminist cinema to documentary practice, experimental film, and even contemporary art installations. Its demonstration that duration and attention could create meaning without traditional narrative structure opened new territories for artistic exploration.

Conclusion: The Radical Ordinary

“Jeanne Dielman” achieves its revolutionary impact through absolute commitment to the ordinary. By treating domestic routine with the same seriousness typically reserved for traditionally masculine subjects—war, business, adventure—Akerman created a new cinematic language capable of honoring women’s experiences in their full complexity.

The film’s power lies not in its argument but in its observation. Rather than telling audiences what to think about women’s domestic lives, it shows them what those lives actually look like when given proper attention and respect. This observational approach allows viewers to reach their own conclusions about the value and difficulty of work that society typically renders invisible.

Forty-eight years after its creation, “Jeanne Dielman” remains uncompromising in its vision and devastating in its implications. It stands as proof that feminist cinema at its best doesn’t simply add women to existing structures but creates entirely new ways of seeing, understanding, and valuing human experience. Through three hours and twenty-one minutes of careful attention to one woman’s life, Akerman created a work that illuminates the lives of countless women whose stories have never been deemed worthy of such sustained artistic attention.

🏆 获奖与荣誉

- • Sight and Sound Greatest Film of All Time 2022年

- • Cannes Directors' Fortnight 1975年

- • Village Voice 19th Greatest 20th Century Film

- • Criterion Collection

⭐ 评分与链接

相关推荐

评论与讨论

与其他观众一起讨论这个视频

加入讨论

与其他观众一起讨论这个视频

评论加载中...