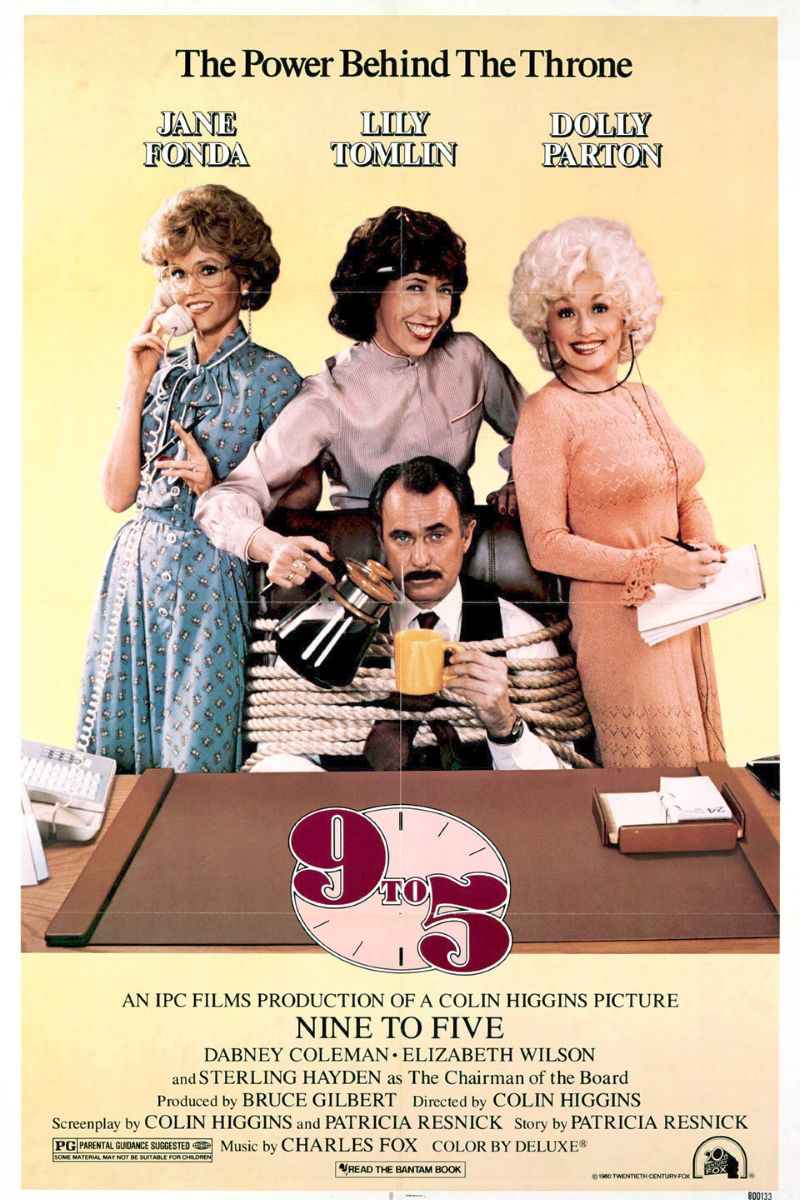

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl

A black comedy drama directed by Zambian filmmaker Rungano Nyoni, starring Susan Chardy. Following young woman Shula who discovers her uncle Fred's body late at night, the film explores the revelation of buried family sexual assault secrets during funeral proceedings with her cousins. With its unique African perspective, the film examines the complex relationships between family trauma, cultural traditions, and women's voices, becoming an important representative work of contemporary African feminist cinema.

主演

🎥 影评与解读

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl represents Zambian director Rungano Nyoni’s powerful follow-up to I Am Not a Witch, a Cannes Film Festival Un Certain Regard competition selection that offers a unique African women’s perspective on the profound exploration of family sexual assault trauma, the duality of cultural traditions, and women’s difficult process of seeking truth and justice within patriarchal family structures. Through Shula’s (Susan Chardy) reaction to discovering her uncle Fred’s body and the subsequent gradual revelation of family secrets during the funeral, the film presents the complex realities facing contemporary African women with delicate yet sharp insight, establishing itself as an important representative work of decolonial feminist cinema.

From an anti-sexual violence perspective, On Becoming a Guinea Fowl’s most important contribution lies in its in-depth exploration and unique presentation of intrafamilial sexual assault trauma. Shula’s calm, even indifferent reaction upon discovering Uncle Fred’s body actually reflects the profound psychological impact of childhood sexual assault experiences. Rather than employing traditional victim narrative modes, the film uses Shula’s “emotional numbness” to demonstrate trauma’s complexity. This treatment challenges social stereotypes about how sexual assault survivors should react, revealing the diversity and individualized characteristics of trauma responses.

The film’s presentation of family funeral traditions carries profound cultural political significance. In Zambian traditional culture, funerals are important moments for family unity and cultural transmission, but the film reveals how such traditional rituals can become tools for concealing family crimes and suppressing survivors’ voices. Uncle Fred’s death triggers traditional mourning rituals, with family members crying and commemorating according to custom, yet Shula and her cousins begin questioning this hypocritical memorial during this process. The film demonstrates the dual nature of traditional culture—both as a source of identity and potentially as a tool for maintaining unjust power relationships.

From a decolonial feminist perspective, the film’s portrayal of African middle-class families is particularly important. Shula’s family represents post-colonial Africa’s emerging middle class, seeking balance between traditional culture and modern values. However, the film reveals that elevated class status does not automatically bring gender equality or eliminate sexual violence. Instead, middle-class families’ concerns about “respectability” and reputation pressure may make issues like sexual assault even more difficult to expose and resolve. This observation challenges developmentalist narratives’ assumptions about modernization necessarily bringing women’s liberation.

Susan Chardy’s outstanding performance provides powerful support for the film’s themes. As a young Zambian actress, she won the British Independent Film Award for Breakthrough Performance with her stunning acting. She successfully presents Shula’s inner complexity—surface calm with internal trauma, contradictory attitudes toward family traditions, and gradually awakening sense of justice. Her performance avoids victim stereotypes, presenting a complex and authentic African women’s image.

The film’s language choice also carries political significance. Most dialogue uses Bemba, a choice that not only enhances the film’s authenticity but more importantly emphasizes the value of African indigenous languages and culture. In a global film industry still dominated by Western languages, this linguistic choice represents resistance to cultural imperialism, embodying decolonialist film practice.

The film’s portrayal of female solidarity and mutual support is particularly moving. Shula’s relationship with her cousins demonstrates how women find mutual support and understanding within patriarchal family structures. Their conversations and interactions reveal their shared challenges and how they gain strength through sharing experiences. This female solidarity is not idealized but formed through difficulty and conflict, making it more authentic and touching.

The film’s visual language is also excellent. Director Nyoni uses Zambian natural landscapes and urban environments to strengthen narrative themes. Nighttime roads, family gathering courtyards, and funeral scenes are all carefully constructed, both showcasing Zambian cultural characteristics and serving emotional expression and thematic presentation. Particularly those shots showing traditional rituals are both beautiful and unsettling, reflecting traditional culture’s complexity.

From a psychological trauma perspective, the film’s presentation of traumatic memory and healing processes is particularly detailed. Shula’s trauma manifests not only as emotional numbness but also in her alienation from family relationships and questioning of traditional authority. The film shows how trauma affects individuals’ worldviews and interpersonal relationships, as well as healing’s complexity and long-term nature.

The film’s treatment of male characters is also interesting. Although Uncle Fred is dead, his presence still dominates the narrative, reflecting perpetrators’ long-term impact. Other male characters—from family elders to younger generations—all participate in or acquiesce to this suppressive system to varying degrees. The film doesn’t simply demonize men but shows how patriarchy shapes everyone’s behavior and attitudes.

From an intergenerational relations perspective, the film shows different generational women’s varying attitudes toward tradition and change. Older women tend to maintain family harmony and traditional values, while younger women are more willing to challenge unjust power relationships. This generational tension reflects universal challenges African societies face during modernization processes.

The film’s title “On Becoming a Guinea Fowl” carries profound symbolic meaning. Guinea fowls are important animals in African culture, having both dietary value and cultural significance. Shula’s “becoming a guinea fowl” might symbolize her transformation from passive victim to individual with agency, or from silence to voice. This transformation is painful but necessary.

The film’s treatment of religion and spiritual beliefs is also balanced. Zambian society is deeply influenced by Christianity while maintaining traditional spiritual beliefs. The film shows how these belief systems can both provide comfort and be used to rationalize unjust behavior. This complex portrayal avoids simple religious criticism, reflecting culture’s multi-layered nature.

From a social stratification perspective, the film shows middle-class families’ special predicament. These families possess certain social status and economic resources, but these advantages haven’t protected women from sexual violence. Instead, pressure to maintain social reputation may make them more silent. This observation is important for understanding gender dynamics among Africa’s urban middle class.

The film’s international recognition is also noteworthy. Its success at Cannes Film Festival and distribution in Britain and America provide important international platforms for African feminist cinema. This recognition affirms not only the film’s artistic value but represents international attention to African women’s voices.

From a philosophical perspective, the film engages with fundamental questions about moral agency, cultural identity, and the nature of justice that are central to African feminist thought. The women’s struggles demonstrate sophisticated moral reasoning while challenging Western feminist assumptions about individual autonomy versus communal responsibility.

The film’s treatment of silence and voice is particularly nuanced. It shows how silence can be both imposed oppression and strategic resistance, while voice can be both liberation and dangerous exposure. This complexity reflects the real challenges facing women in transitional societies.

Ultimately, On Becoming a Guinea Fowl’s value lies in its authentic and complex presentation of African women’s experiences. Through Shula’s story, the film demonstrates family trauma’s profound impact, cultural traditions’ duality, and women’s difficulty and courage in seeking justice. It contributes a unique African women’s perspective to world cinema, challenging simplified narratives about trauma, family, and culture. In the context of global anti-sexual violence movements, such works remind us that women’s experiences have cultural specificity, requiring understanding and response within specific social-cultural contexts. Simultaneously, it demonstrates the universality of women’s strength—regardless of cultural background, women struggle for dignity, truth, and justice.

🏆 获奖与荣誉

- • 戛纳电影节 Un Certain Regard

- • 英国独立电影奖 Breakthrough Performance

- • 英国独立电影奖 最佳导演 提名

⭐ 评分与链接

相关推荐

评论与讨论

与其他观众一起讨论这个视频

加入讨论

与其他观众一起讨论这个视频

评论加载中...