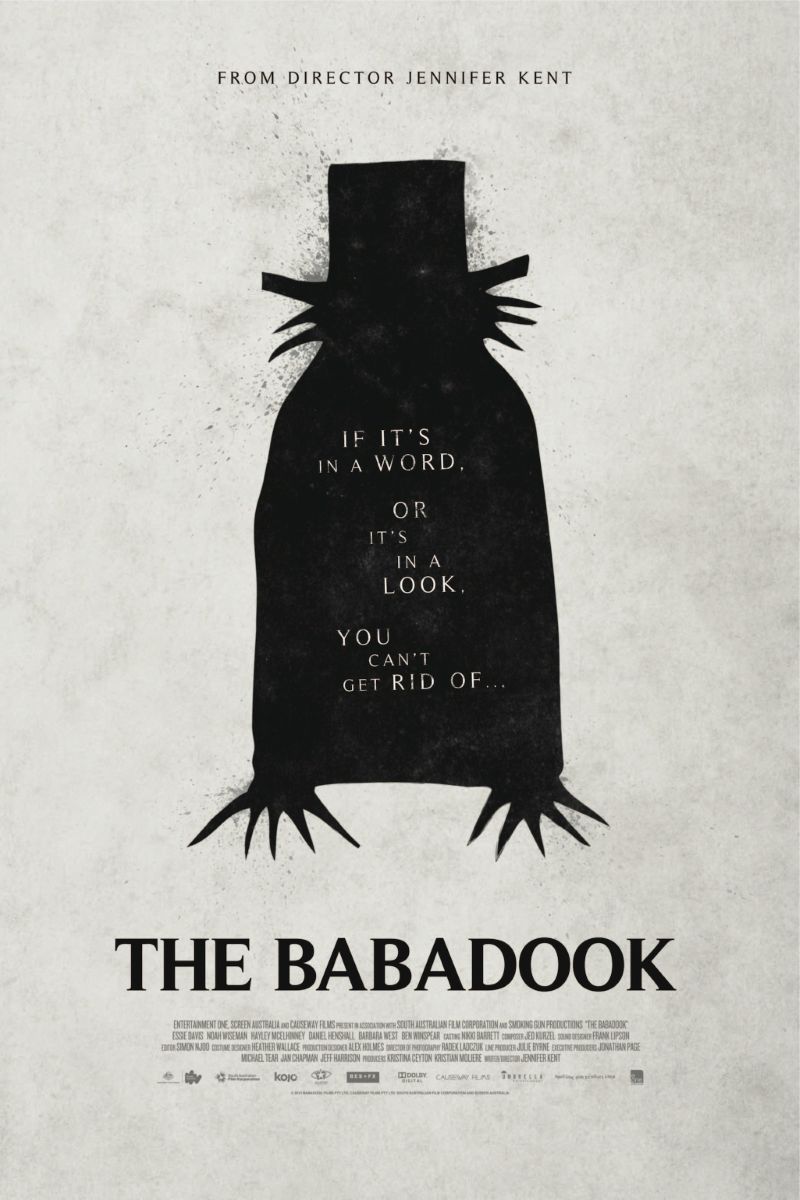

The Babadook

The Babadook

A widowed single mother Amelia and her young son confront the mysterious terror creature Babadook in their home. This Australian psychological horror film breaks traditional gender stereotypes in horror cinema, exploring profound themes of loss, grief, maternal stress, and women's inner darkness from a mother's perspective.

主演

🎥 影评与解读

“The Babadook” stands as a milestone in feminist horror cinema, with director Jennifer Kent employing her keen female perspective to create a profound allegory about motherhood, grief, and psychological trauma. This film not only subverts traditional horror film stereotypes about female characters but bravely reveals the dark aspects of maternal experience that society considers taboo, providing an unprecedented cinematic text for understanding women’s psychological complexity.

The film’s core lies in its complete deconstruction of the “perfect mother” myth. Amelia (Essie Davis) is not an ideal mother in traditional terms—she’s exhausted, angry, filled with resentment, and even harbors impulses to harm her own child. This portrayal is extremely taboo in mainstream culture, as society expects mothers to embody unconditional love and devotion. Kent rejects this romanticized notion of motherhood, instead presenting the authentic face of maternal experience: a complex journey filled with challenges, loneliness, and internal conflicts.

From feminist psychology perspectives, the Babadook monster itself serves as a brilliant psychological metaphor. It represents suppressed grief, anger, and trauma—emotions that patriarchal society often requires women to hide or deny. When society tells women they must be “strong,” “maternal,” and “selfless,” these forbidden emotions take root in the depths of the psyche like the Babadook, eventually erupting in distorted forms.

The film’s treatment of loss and grief carries profound feminist implications. Amelia’s trauma from losing her husband isn’t merely personal tragedy but reflects women’s vulnerable position in patriarchal society. When she becomes a single mother, she must bear economic pressure, childcare responsibilities, and emotional burdens alone, while society provides little genuine support system. This isolated helplessness intensifies her psychological pressure, preventing grief and anger from finding healthy release.

Essie Davis’s performance represents a perfect interpretation of women’s emotional complexity. She doesn’t portray Amelia as simply a victim or hero but presents an authentic, contradictory female image. Her exhaustion is real, her anger is justified, her fear is understandable. This multilayered performance challenges audiences’ preconceptions about motherhood, forcing us to reconsider what constitutes a “good mother.”

The film’s treatment of child characters also offers a unique feminist perspective. Sam isn’t the innocent child needing rescue in traditional horror films but an equally complex individual. His behavioral problems, dependence on his mother, and longing for his father all reflect the complex dynamics of mother-child relationships in single-parent families. Kent doesn’t idealize children but presents realistic challenges and emotional conflicts in parenting.

From emotional labor perspectives, “The Babadook” reveals the invisible emotional work women undertake. Amelia must not only process her own grief and trauma but manage her son’s emotional needs while maintaining a facade of “everything’s fine” in society. This multiple emotional burden is often invisible yet consumes enormous psychological energy from women.

The film’s visual design is rich with symbolic meaning. Dark tones, oppressive interior spaces, and distorted imagery all reflect Amelia’s inner state. The house itself becomes a metaphor for psychological space—closed, dark, threatening, yet simultaneously refuge and battleground. This spatial design embodies the contradictory situation of women being both protected and constrained within domestic spaces.

The film’s critique of absent social support systems also bears distinctly feminist colors. People around Amelia—neighbors, friends, colleagues—either cannot understand her situation or offer superficial help. This isolation reflects society’s systematic neglect of single mothers and disregard for women’s emotional needs. When women display vulnerability or negative emotions, they’re often labeled as “incompetent” or “problematic.”

From mental health perspectives, the film’s depiction of postpartum depression and grief-related sadness carries important social significance. Amelia’s symptoms—insomnia, irritability, isolation, contradictory feelings toward her child—are real mental health issues. However, society often stigmatizes these symptoms, believing “good mothers” shouldn’t have such feelings.

The film’s ending deserves particular analysis. The Babadook isn’t completely eliminated but controlled and managed. This treatment reflects realistic understanding of psychological trauma—trauma and grief don’t completely disappear but can be learned to coexist with. Amelia learns to acknowledge and manage her dark emotions rather than suppress or deny them. This growth process embodies the development of women’s psychological resilience.

From mother-child relationship perspectives, the film presents a more honest and complex model of affection. Maternal love isn’t innate or unconditional but must be achieved through struggle, understanding, and growth. Amelia and Sam’s relationship experiences crisis and repair, ultimately reaching a more authentic and healthy balance.

The film’s treatment of female sexuality and desire also carries feminist significance. Amelia’s sexual needs and longing for intimate relationships aren’t ignored or shamed but recognized as normal components of humanity. This treatment challenges social expectations that “mothers should be desexualized,” acknowledging women’s multiple identities and needs.

“The Babadook” also explores the legitimacy of female anger. In patriarchal society, women’s anger is often viewed as inappropriate or threatening emotion, particularly maternal anger. However, the film demonstrates that anger can be a legitimate emotional response, even a catalyst for self-protection and growth. Amelia learns to transform anger into strength, using it to combat threats and protect herself and her child.

From cultural criticism perspectives, the film’s depiction of Australian middle-class life reveals psychological crises hidden behind seemingly safe suburban environments. This critique targets not only specific social environments but reflects universal dilemmas women face in modern society—external material security cannot guarantee internal psychological health.

The film’s sound design also deserves attention. Harsh sounds, low tones, and sudden silences all embody the auditory experience of trauma and anxiety. This sound design not only creates horror atmosphere but simulates the internal experience of psychological trauma patients, enhancing audience empathy for Amelia’s situation.

From intergenerational trauma perspectives, the film suggests how trauma transmits within families. Amelia’s pain inevitably affects Sam, while Sam’s behavioral problems intensify Amelia’s pressure. This vicious cycle reflects how unprocessed psychological trauma affects family dynamics and child development.

The film’s exploration of female friendship and community support reveals the importance of women’s networks while acknowledging their limitations. The few supportive relationships Amelia maintains—with her sister-in-law, certain colleagues—provide glimpses of what adequate support might look like while highlighting how rare such understanding truly is.

Jennifer Kent’s directorial approach demonstrates remarkable confidence in centering female subjectivity. The film never judges Amelia for her “failures” as a mother but instead contextualizes her struggles within larger systemic issues. This empathetic approach distinguishes feminist horror from traditional horror that often punishes women for stepping outside prescribed roles.

The film’s treatment of class dynamics adds another layer of complexity. As a middle-class widow, Amelia has certain privileges—homeownership, some financial stability—yet these advantages cannot protect her from psychological suffering. This portrayal avoids both romanticizing and dismissing the very real impact of economic factors on mental health.

“The Babadook’s” international success proves the market potential and cultural influence of feminist horror films. It demonstrates that audiences hunger for more complex and authentic female characters, not merely victims or saviors in traditional horror films. This success paved the way for more female directors and feminist-themed horror films.

Ultimately, “The Babadook’s” value lies in its honest portrayal of women’s psychological complexity and brave exploration of socially taboo topics. It tells us that acknowledging and facing our inner darkness isn’t weakness but a necessary step toward growth and healing. In a society that still demands women play perfect roles, this film provides a more humanized and sustainable model of female growth, encouraging women to embrace their wholeness, including emotions and needs society deems “inappropriate.”

🏆 获奖与荣誉

- • 戛纳电影节 Directors' Fortnight Best New Director Award

- • Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts Award 最佳导演

- • Sydney Film Festival Best Australian Film

- • Toronto International Film Festival Screening

⭐ 评分与链接

相关推荐

评论与讨论

与其他观众一起讨论这个视频

加入讨论

与其他观众一起讨论这个视频

评论加载中...