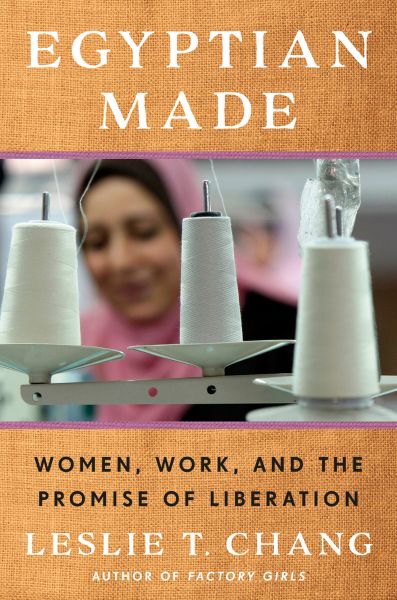

Egyptian Made: Women, Work, and the Promise of Liberation

From the author of Factory Girls, a two-year investigative report revealing how globalization's promise of liberation paved the way for oppression. Follow three Egyptian women navigating between traditional culture and modernization demands.

📝 Book Review

When the wave of globalization swept across the world, it carried a seductive promise: economic development would bring liberation to women, and work would become a pathway to autonomy and independence. Yet in Egypt—a country with thousands of years of civilization struggling to reconcile traditional culture with modernization demands—the fulfillment of this promise proves far more complex than imagined. In “Egyptian Made,” Leslie T. Chang, through two years of immersive reporting, tracks three Egyptian women’s struggles in the workplace, home, and society, revealing a brutal reality: globalization has not only failed to liberate women but has in many ways paved the way for new forms of oppression.

Chang is no stranger to these issues. As the author of “Factory Girls,” she once delved into factories in southern China, documenting the lives and dreams of young female workers in the global supply chain. That book demonstrated her core capabilities as a journalist: long-term fieldwork, keen observation of individual lives, and the analytical capacity to connect micro-stories with macro economic and political forces. In “Egyptian Made,” she brings these skills to a radically different cultural and political environment. She lived and worked in Egypt for five years, learning Arabic, building trust relationships, and gaining intimate knowledge of women’s daily lives—from factory floors to family living rooms, from marriage negotiations to divorce courts.

This book focuses on Egypt’s historic textile industry—an industry once glorious, now struggling to survive. The textile industry has centuries of history in Egypt and was once a pillar of the national economy. But in the era of globalization, facing fierce competition from countries like China and Bangladesh, Egypt’s textile industry has fallen into crisis. Government policies vacillate, infrastructure is outdated, the education system has failed—all of this places the industry and the women working within it in an extremely vulnerable position. Chang chose the textile industry as her observation point not only because it employs large numbers of women, but because it is a microcosm of globalization’s impact on developing countries.

The book’s first protagonist is Riham, a shrewd businesswoman running her own garment factory. In a society where female entrepreneurs are extremely rare, Riham’s very existence is a challenge. She must navigate male-dominated business networks, dealing with skepticism and resistance from family, community, and even employees. But her greatest challenge comes from the economic structure itself: she struggles to recruit employees willing to work in factories—because factory work is heavily stigmatized in Egypt, especially for women. She also struggles to compete in the global market, as Egypt’s production costs are higher than many competitors, and she cannot access sufficient financial and technical support to enhance competitiveness.

Chang meticulously documents Riham’s daily struggles: negotiating with suppliers, trying to convince banks to grant loans, handling workers’ complaints and conflicts, balancing family responsibilities with career ambitions. Through Riham’s story, we see the structural barriers female entrepreneurs face in developing countries. This is not merely a “glass ceiling” issue—though gender discrimination certainly exists—but rather a problem with the entire economic and political system. When government policies change constantly, when laws are poorly enforced, when the financial system favors large enterprises and politically connected companies, small entrepreneurs—especially women—have almost no chance of success.

The second protagonist is Rania, a factory assembly line worker aspiring to advance to management. Rania represents the larger majority of Egyptian female workers: she is not the boss but an employee, depending on wages for survival. Rania is intelligent, hardworking, and ambitious—by all rights, she should be able to advance. But she faces multiple obstacles: conflicts with colleagues—partly from workplace competition, partly from jealousy of her ambition; management’s gender bias—they believe women are unsuited for leadership positions; and her own unfortunate marriage—her husband’s humiliation and control drain her energy and confidence.

Chang shows how work is both a possibility for liberation and a site of oppression. For Rania, factory work provides an opportunity for economic independence, allowing her to leave an abusive marriage and support herself and her children. But at the same time, the factory is a place full of exploitation and humiliation: low wages, long hours, terrible conditions, sexual harassment, and constant degradation from management and colleagues. Worse still, the stigma of factory work means Rania’s status in the community declines—in traditional views, “good women” should stay at home, not work in factories alongside men. Rania struggles to maintain her dignity, insisting on the value of her work, but social prejudice continually erodes her self-esteem.

The third protagonist is Doaa, Rania’s colleague, who pursues education and independence but must sacrifice custody of her children to obtain a divorce. Doaa’s story reveals the brutal reality of Egyptian family law. In Egypt, women can initiate divorce, but the price is high: they typically must forfeit financial compensation, and more painfully, may lose custody of their children. Traditionally, children are seen as belonging to the father’s family, with mothers having extremely limited rights. Doaa deeply loves her children, but her marriage has become unbearable. She faces a cruel choice: remain in an oppressive marriage or pursue freedom but lose her children.

Doaa chose divorce, bearing the immense pain of losing her children. She threw herself into work and education, trying to build a new life by acquiring skills and qualifications. But her wound never truly healed. Chang sensitively documents Doaa’s inner struggle: her longing for freedom, her yearning for her children, her anger at social injustice, and her efforts to find meaning in her choices. Doaa’s story poses a profound question: when the cost of freedom is so high, when social structures force women to choose between different forms of suffering, can we still say they are “free”?

These three women’s stories interweave to sketch the complex predicament facing Egyptian women. They are not passive victims—each resists, adapts, and negotiates in her own way. Riham uses business acumen and networking; Rania persists in working, refusing to be crushed by humiliation; Doaa pursues education, seeking ways to rebuild her life. But their individual agency is severely constrained by structural forces: global economic inequality, failed state policies, patriarchal cultural constraints, discriminatory legal systems.

Chang not only documents individual stories but deeply analyzes these structural forces. She traces the history of Egypt’s textile industry, from the colonial period through independence, from Nasser’s socialist experiments to Sadat’s open-door policies, to Mubarak-era neoliberal reforms and post-2011 revolution political turmoil. Each policy shift has profoundly affected the textile industry and female workers. During the Nasser era, the state promised full employment and social welfare, factory work was relatively stable; during the Sadat and Mubarak eras, privatization and marketization led to massive worker layoffs, remaining workers faced worse conditions; after the revolution, economic chaos and political instability further deteriorated the situation.

Chang also explores Islam’s historical and contemporary role in Egypt. She carefully distinguishes different forms of Islamic practice and interpretation, avoiding simplistic stereotypes. She shows how Islam can be both a source of women’s oppression—through conservative interpretations of women’s roles, behavior, and rights—and a resource for women’s agency—by providing moral frameworks and community support. The women in the book are all Muslim, but their relationships with religion vary. Some find solace and strength in religion, some question religious restrictions on women, some seek balance between tradition and modernity.

One important theme of the book is the failure of the education system. Egypt invests substantial resources in building schools, literacy rates have improved, but educational quality is abysmal. Students memorize by rote, critical thinking is suppressed, teacher qualifications are low, school facilities are dilapidated. More importantly, educational content is disconnected from labor market demands. University graduates find what they learned useless at work, while employers complain they cannot find qualified workers. This disconnect between education and employment particularly affects women, who already face more employment barriers, and poor education further limits their options.

Marriage and family relations are another key dimension. In Egypt, marriage is not merely personal choice but a social and economic contract involving alliances between families, property transfers, and establishment of social status. Women are at a disadvantage in the marriage market: they are expected to be young, virgin, obedient, while men are allowed more freedom and power. Once marriage is established, women’s choices become even more constrained. While divorce is legally possible, social stigma and economic consequences make it an extremely difficult choice. The women in the book all struggle with marriage’s constraints—whether trying to negotiate more autonomy within marriage or trying to escape oppressive marriages.

Chang also shares her own experiences as a foreign journalist and woman living in Egypt. She honestly reflects on her own privilege and limitations: as an American, she possesses freedoms and resources unimaginable to Egyptian women; but as a woman, she also experienced gender discrimination and harassment, though in different forms and degrees than Egyptian women. She describes being stared at and verbally harassed on the street, and the relative safety enjoyed as a married woman (she wore a wedding ring while in Egypt to avoid some harassment) compared to single women. These personal experiences deepened her understanding of the risks and restrictions Egyptian women face daily.

The book’s power lies in its refusal of simplistic narratives. Chang does not present Egyptian women as helpless victims, nor does she romanticize them as heroic resisters. She shows their complexity: their strength and vulnerability, their ambitions and compromises, their resistance and compliance. She also does not simplistically oppose “tradition” versus “modernity,” “religious” versus “secular,” “East” versus “West.” She shows how these categories interpenetrate in reality, how they are utilized and redefined differently by different people.

Chang’s critique of globalization is particularly sharp. She reveals how global supply chains exploit labor in developing countries, especially female labor. When Western consumers buy cheap clothing, they rarely think about how and under what conditions these clothes were produced. Globalization’s promise is shared prosperity through trade and investment, but the reality is wealth and power highly concentrated in a few countries and companies, while most workers—especially female workers—bear extremely low wages, terrible conditions, and unstable employment.

But Chang also avoids a simplistic anti-globalization stance. She recognizes that for the women in her book, factory work—despite all its problems—may still be the best option available to them. It provides the possibility of economic independence, allowing them to escape more oppressive family arrangements. The problem is not globalization itself, but the specific form of globalization: one that prioritizes profit over people, reinforces rather than challenges inequality. Chang suggests another form of globalization is possible—one that truly respects workers’ rights, supports economic justice, and promotes gender equality—but this requires fundamental political and economic transformation.

The book’s final section is particularly thought-provoking. Chang does not offer simple solutions or optimistic conclusions. She honestly acknowledges that the lives of the women she tracked continue to struggle after she left Egypt. Riham’s factory still struggles on the survival line; Rania still battles workplace discrimination and marriage trauma; Doaa still misses her children, striving to find meaning in her sacrifice. But Chang also documents their resilience and dignity. Despite facing enormous obstacles, they continue to work, continue to dream, continue to fight for better lives for themselves and their daughters.

“Egyptian Made” is a profound book about work, gender, and globalization, but it is also a book about human dignity and agency. While documenting structural oppression, Chang also captures the richness and complexity of individual lives. We see Riham’s shrewdness in business negotiations and her tenderness at family gatherings; we see Rania’s resilience in the factory and her vulnerability facing humiliation; we see Doaa’s hunger for education and her longing for her children. These women are not statistics or case studies, but whole human beings whose lives deserve to be seen, understood, and respected.

This book is also a challenge to all of us. If we truly care about gender equality and economic justice, we must go beyond superficial “empowerment” discourse and seriously confront structural inequality. We must question the global economic system, challenge unjust trade policies, support worker organizing and collective action. We must recognize that “liberation” cannot be achieved merely by bringing women into the labor market, but must be accompanied by transformation of work itself, revaluation of care labor, and fundamental reconstruction of gender relations.

Leslie T. Chang’s “Egyptian Made” continues the project she began in “Factory Girls”: giving voice to the women often overlooked in global supply chains. But this book goes further—it not only documents their lives but analyzes the historical, political, and economic forces shaping these lives. It is an outstanding example of feminist anthropology and an important contribution to critical thinking about globalization. For anyone concerned with women’s rights, labor justice, and global inequality, this book is essential reading. It reminds us that liberation is not a goal that can be automatically achieved through market forces, but a political project requiring sustained struggle, structural change, and genuine solidarity.

Book Info

Related Topics

🛒 Get This Book

Buy on Amazon

Buy on Amazon Related Books

Book Discussion

Share your thoughts and opinions on this book and exchange insights with other readers

Join the Discussion

Share your thoughts and opinions on this book and exchange insights with other readers

Loading comments...