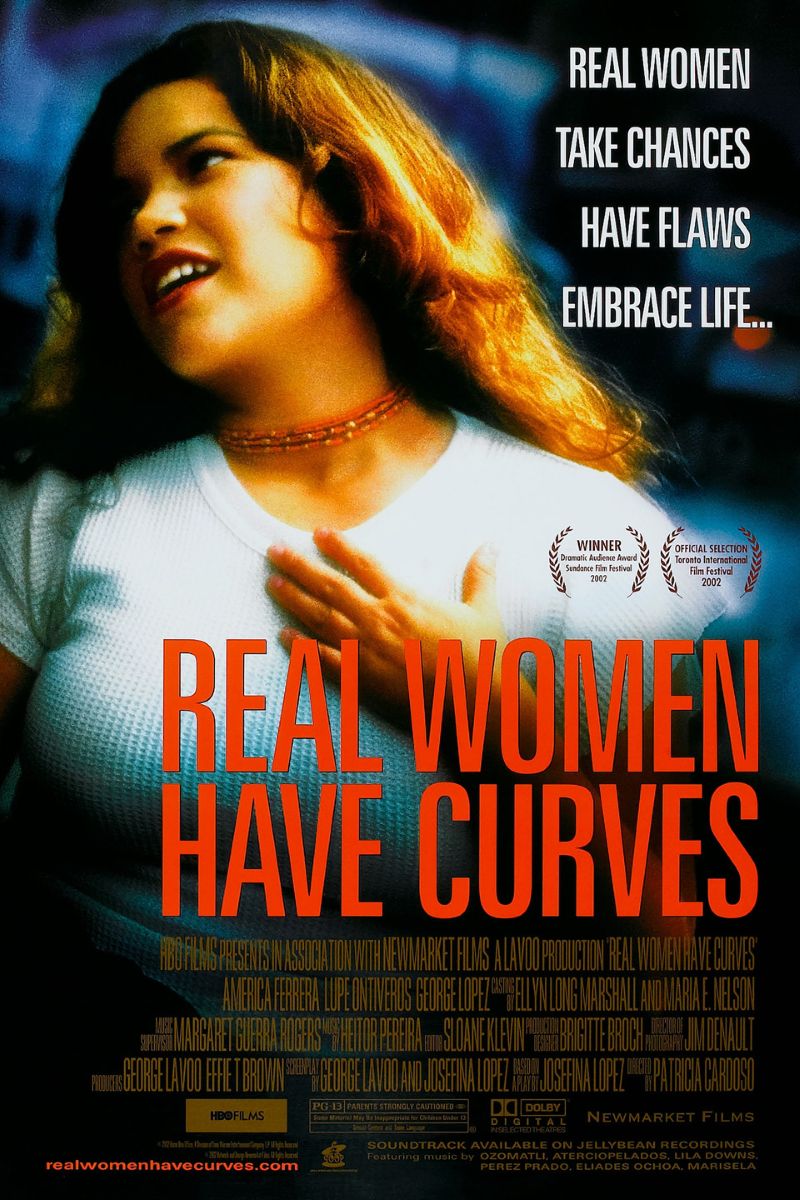

Real Women Have Curves

Real Women Have Curves

18-year-old Mexican-American Ana García struggles between her college dreams and traditional family expectations. This groundbreaking independent film explores themes of body autonomy, cultural identity, class mobility, and intergenerational conflict through a Latina lens, becoming a milestone in the body positivity movement and Latina feminist cinema.

Cast

Related Topics

🎥 Film Analysis & Review

Real Women Have Curves stands as a groundbreaking work in early 21st-century Latina feminist cinema, with director Patricia Cardoso becoming the first Latina woman to win the Sundance Film Festival Audience Award. Adapted from Josefina López’s play of the same name, this film marks not only America Ferrera’s screen debut but also a milestone in body positivity movements and Latina narratives. Through the coming-of-age story of 18-year-old Mexican-American Ana García (America Ferrera), the film profoundly explores complex themes of intersectional oppression, body politics, cultural identity, and class mobility.

From an intersectional feminist perspective, Ana’s identity reveals multiple dimensions of complexity. As a first-generation daughter of immigrants, she is simultaneously Mexican-American, working-class, and a young woman aspiring to higher education. This intersection of identities reaches a dramatic climax in her conflict with her mother Carmen (Lupe Ontiveros). While her mother insists on traditional gender role expectations—marriage, children, working in the family sewing factory—Ana yearns to transcend class boundaries through education. This conflict goes beyond simple generational differences, reflecting deep contradictions within Latino communities regarding gender, class, and cultural heritage.

The film’s most revolutionary contribution lies in its radical expression of bodily autonomy. In an iconic scene, Ana and other female workers strip down in the sweltering factory, displaying and celebrating their “imperfect” bodies. This moment represents not just open rebellion against mainstream beauty standards, but a symbol of collective awakening. By showcasing real, diverse female bodies, the film directly challenges Hollywood’s stereotypical and sexualized portrayals of Latina women. As scholar Juanita Heredia notes, these Latina protagonists represent autonomous voices resisting the institutionalization of patriarchy in family structures and labor markets.

Through the lens of class analysis, the sewing factory becomes a social microcosm full of contradictions. It represents both immigrant women’s economic independence and collective support system, while also symbolizing limited choices and exploited labor. López’s original play deeply explores how multiple oppressions based on class, gender, race, and immigration status interweave by depicting workplace relationships. The film emphasizes the simultaneity and interconnectedness of these oppressions, revealing how immigrant status exacerbates gender and class inequalities.

The mother-daughter relationship forms the film’s emotional core. Carmen’s constant criticism of Ana’s body—calling her too fat, unattractive—reflects how internalized patriarchal beauty standards are transmitted between women. However, the film avoids simply demonizing the mother, instead showing her complexity: she is both an enforcer of oppressive traditional values and a victim of those same values. The factory workers’ conversations demonstrate a process of consciousness-raising that can be understood as collective feminist consciousness-building practice.

From an educational equality perspective, Ana’s acceptance to Columbia University transcends personal success to become a challenge to systemic inequality. As the child of undocumented immigrants, she bears responsibility for protecting her family from immigration authorities. This tension between responsibility and educational pursuit reveals how immigrant status complicates upward mobility possibilities. The film shows education as not merely a tool for economic mobility but a pathway to identity and self-realization.

The film’s subversion of media representation holds profound significance. It rejects traditional stereotypes of Latina women—exotic sex objects or submissive victims—presenting complex, multidimensional female characters. The film won the 2002 Sundance Audience Award, Special Jury Prize for Acting, and Independent Spirit Award for Best Debut Performance. Entertainment Weekly called it “one of the most influential movies of the 2000s,” noting it “paved the way for a new generation of filmmakers.”

From a body politics perspective, the film celebrates fuller bodies in a culture that worships thinness, challenging mainstream narratives about health, beauty, and value. This body positivity theme was not prevalent in media at the time, especially for women of color. The film’s bold declaration that “women can be any size or shape and deserve respect” was revolutionary for its time. It revealed how fatphobia affects self-esteem and family dynamics while reinforcing unrealistic standards from cultural traditions.

Cultural identity negotiation forms another key theme. Ana’s journey isn’t about rejecting her Mexican heritage but critically engaging with and redefining these traditions. She learns to distinguish which cultural values are worth preserving and which need challenging. The film shows how second-generation immigrants navigate multiple cultural expectations, creating hybrid, fluid identities. This identity fluidity itself becomes a form of resistance, challenging essentialist notions of authenticity and belonging.

From a family liberation perspective, Ana must break traditional family expectations to pursue self-realization. The film shows how family can be both a source of support and limiting shackles. Ana’s ultimate choice to leave for college isn’t betraying her family but being true to herself. This choice reflects the dilemma many immigrant children face—balancing respect for family traditions with pursuing personal dreams.

The film’s exploration of immigrant identity holds special significance. As an American-born citizen, Ana enjoys opportunities her parents lack while bearing unique responsibilities. She must bridge two cultures, maintaining respect for Mexican traditions while embracing American opportunities. This dual cultural identity negotiation process reflects the shared experience of millions of Latino Americans.

From a female friendship perspective, relationships between factory workers demonstrate the power of female solidarity. Despite differences in age, experience, and viewpoints, their shared work environment and gender experiences create a foundation for understanding and support. Particularly in the body acceptance scene, the workers’ mutual support and celebration show possibilities for collective female empowerment.

The film’s aesthetic choices serve its political themes. Naturalistic cinematography, authentic East Los Angeles locations, and non-Hollywood body presentations all reinforce the film’s authenticity and political stance. These aesthetic choices reject commercial cinema’s glossy packaging, choosing instead to present the real lives of working-class Latino communities.

From a contemporary perspective, the film’s legacy continues today. It paved the way for subsequent Latina feminist films, proving that stories centering women of color have universal resonance. America Ferrera became an icon for many young women, especially Latinas. However, it’s unfortunate that this landmark work didn’t advance Cardoso’s directorial career as expected, reflecting Hollywood’s persistent systemic barriers.

The film’s depiction of labor also carries feminist significance. Factory sewing work is both economic necessity and expression of women’s skills and creativity. The film doesn’t romanticize this labor but shows both its hardship and value. The workers’ manual skills represent undervalued expertise; their labor supports family economies yet rarely receives due recognition.

From a mental health perspective, the body shaming and cultural pressure Ana faces profoundly impact her psychological well-being. The film shows how these pressures lead to self-doubt and internal conflict while demonstrating how self-acceptance and external support help her overcome these challenges. This portrayal emphasizes mental health’s importance in the female empowerment process.

The film’s treatment of intergenerational trauma also deserves attention. Carmen’s harsh expectations for Ana partly stem from her own unrealized dreams and limited opportunities. This emotional transmission between generations shows how patriarchy perpetuates itself through family structures. Ana’s rebellion represents not just personal liberation but an attempt to break this trauma cycle.

Ultimately, Real Women Have Curves transforms intersectional feminist theory into accessible emotional narrative. The film creates a space where marginalized voices are not just heard but celebrated. It reminds us that true feminist cinema isn’t about simple formulas for “strong female characters” but presenting the complexity, contradiction, and authenticity of women’s experiences. In a world that continues to link women’s value to appearance, the film’s message—that real women have curves, stories, dreams, and autonomy—remains profoundly revolutionary.

🏆 Awards & Recognition

- • Sundance Film Festival Audience Award

- • Sundance Special Jury Prize for Acting

- • Independent Spirit Award for Best Debut Performance (America Ferrera)

- • Young Artist Award for Best Leading Young Actress

⭐ Ratings & Links

Related Recommendations

Comments & Discussion

Discuss this video with other viewers

Join the Discussion

Discuss this video with other viewers

Loading comments...